If the dull sounds of love hadn’t rumpled the silence, one would have heard the falling snow. Behind the large bay window, he was nude, the woman close. She was naked too, and, limbs akimbo, had given up her soft form to the hard angles of the room.

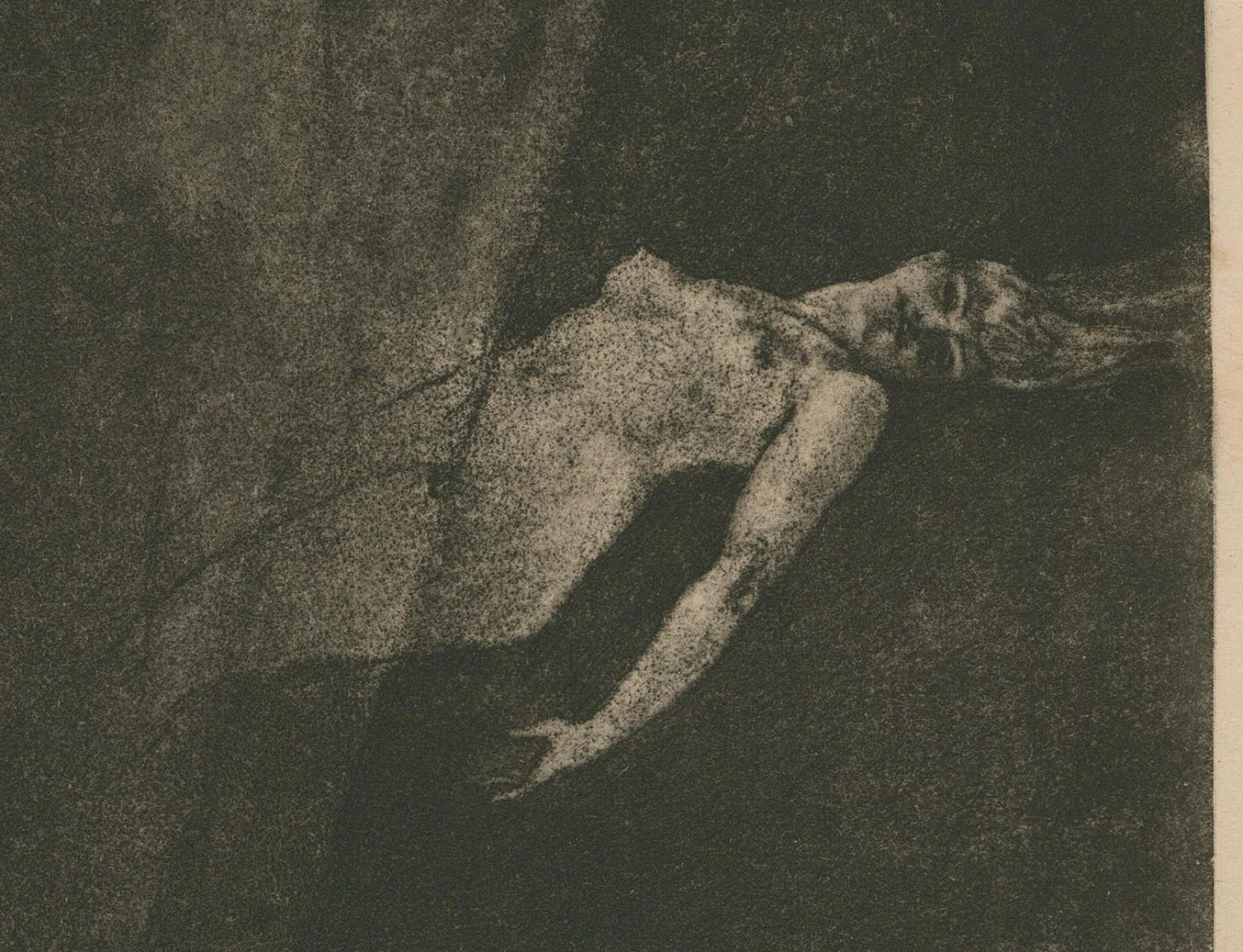

The body, placed on a bed of black marble, was laid out on its back, neck neatly set against the cold surface. Her abundant hair, falling freely over the marble, cut across the ivory oval of her face. The man was visibly struggling to decipher her impassive features. His eyes, worn out by the snow, blinked over the whiteness of her stomach. It was already late, and the vast space, open to the seasons along one side, confounded the passing of the hours. With their bodies unmoving, the stone altar, as the day came to its end, took on the appearance of a classical composition: some Venus, eternally seduced in plaster, in the depths of a museum iced with the rare objects dispersed throughout its rooms. The slack muscles of the woman, having earlier burnt with the fever of her agonies, now gently contracted in the unheated chamber. Her mouth opened onto her tongue and incisors as though to pronounce the wet syllable from which a complicit word would begin to take shape. The man caressed her stomach and probed her black sex without taking his eyes from that mouth with its pearly little teeth. The woman was still beautiful, with a sure and distant beauty, having been superbly so, as though her past perfection were magnified in being nothing more than a memory now. The man’s bony hands sought entry into the turned and returned body. His fingers pinched its silky skin, taut over the thickness of the breasts and thighs. They sank into its openings, as though applied to a torture reduced to its perverse dimensions. The man passed an arm around her waist and half-lifted the body. He was surprised by the nude’s weight, the strange presence of flesh, and the shadows that had drawn him into his domain. He took her little foot in his palm and moaned, as though trying to break free from an invisible embrace. For a long time after his sperm had covered her thighs and groin, he delicately polished her stomach with the substance, until her skin was permeated deeply with its swirling burnish. He then lay his head between her thighs and seemed to sleep a while. The snow slumped down the other side of the glass, thick and heavy, blending sudden flurries, in which vague monochrome figures were sketched, with his tedious idling. Such whiteness blinded, perceptibly holding back the night. The subtle anaesthesia of the air froze the embracing couple in place, while darker shades accentuated the absurd games the strange relief played with line and volume, the knotting of their ropes of flesh. Certain hours do not pass, going back over centuries. Solitude so complete the line of wakefulness gets mislaid. The past hollows with an organ blast. Every gesture suddenly takes on the forms of a mausoleum of stupefaction, wherein seconds are stones. With his face buried in the reclining shadows, the man thought he was dreaming when he had done nothing but cause time to overflow. Suddenly, he seemed to emerge from this consciousness as though from a delicious coma, finally escaping the terrible insomnia in which his existence had unfolded as though he were in a daze.

The sweetness of unshared hours. Isolation does not fear the silence of footsteps in the snow if the body is vibrating sufficiently with the deep din of desire. The air is thick, but like a body between bodies. The slope that opens to memory is gentle … The first is that of a stairway to the sea. A lone woman descends it onto a spit of sand, then her feet disappear, and her thighs glimmer in the sunset as she lifts her dress higher, higher than the waves, higher than memory.

For years he had lived in peace in a large house on the coast. The horizon was his childhood garden and the beaches the construction site of fabulous castles laid waste by the tides. For how many infinite mornings does childhood endure when viewed from the gloomy afternoon of age? He would walk the trim of breakers, the length of a trail of seaweed and maritime flowers. The mansion overlooking the banks, and from which he was certainly being watched, was square at his back, more secure than his shadow. Level with the flats, facing the dunes where forts and masts drew a mournful widow’s murmur from the wind, it appeared as some kind of advanced semaphore amid the oblique silence and the quivering of necklines that precedes the waves’ engorgement. On certain drizzly evenings, elements of the landscape confused themselves with the pure lines of the horizon, ending up in a black water from whose despondency nothing could escape. The roar of the swell overwhelmed even the cracking of logs and the squawking of the gulls. At that hour, the swaying of the backwash numbed, and everything became simple. But sleep came late to the upper mansard. While the lamp burnt, the child, stunned by solitude, was mithered by the great noise of that mouth from which no word was ever loosed to break the spell. Books opened like skylights quickly foreclosed by the foggy monsters of the open sea, taking up the horizon with their phantasmagoria. The devotion of a mother and of a woman, beautiful and alone, remained, faithful to the tides as to the sun or the moon. She descended to the ebb tide collecting fruits and stars. In his turn, the child kept his eyes on her from the window: dropping into the ravines, tiny amid the foam. She would often freeze, black veil stiff against the wind. Hair undone, turned toward the rumble, she seemed to call on the invisible to take its place. And the child trembled from loneliness and fright. Absence is that distance wherein the body gets stuck, but which leaves a taste of eternity beyond all rupture on the lips. More odious than absence are certain exclusions, stalling in contemplation of an incomprehensible third-party. The child would breathe heavily when his mother broke down in usurping reveries, while, in the same moment, offering the miraculous whiteness of her thighs to the waves splashing around her, in the folds of twilight, between the crystalline sky and the roving shadows, the golden vessels that sometimes loomed, holding by a thread dreams of islands and crossings without return.

The child grew up within a blink of his world’s eye. The house always appeared as vast and the horizon as close to infinity, but little by little emptiness pressed within him hollowing his memory, like a sandcastle disappearing in large swathes, leaving here and there fragments of wonder, absurd ruins. The faceless expanses, the calm incarnations of the seasons, were followed by the routing of the towns and the swamping of the suburbs. The child aged happily among the wreckage. Forgetful actor, he mimed scenes past, gesticulating when the text was missing, to the stupefaction of the odd witness. He put years into discovering a clandestine balance thanks to the various substitutes society offers for impractical desires. It is no rare coincidence to find a sadist in the white coat of a surgeon or a voyeur at foundations of their goals. Nevertheless, he sometimes returned to the high mansion of brick and pebble, which had to be dried out with fire so much did the damp seep into the rooms, their wooden shutters closed for entire seasons. It was still aloof behind his back, though blind now, no longer bearing his mother’s gaze. He liked to think, nonetheless, about the great solitude of the tides and of that abrupt building throughout time, like a stubborn dream sent back to the remote lands of memory …

Finally, the man woke up. Sitting close to the woman, he scrutinized the room with a sweeping and suspicious look. He froze again in contemplation of the snow. Thick and slow, like a sheet endlessly falling. Suddenly weary, he stretched alongside the laid out woman and sighed heavily. His hands rediscovered their blind trade, coming to a stop at her breasts, which spilled over fingers eager to hold them. He lifted the woman’s hand and placed it back on his sex, which subsided under its pressure. White, it covered only the penis, haloed by black locks, and so evoked her pale face amid her hair. Little by little, his blood rose, lifting, in a few pulses, the middle then index fingers, finally allowing the glans to swell, stiff as another finger. The hand slid slowly down to the pubis and appeared to softly encircle the base of his sex. They stayed like that for some time, him tense in his desire, the other still open and slack, as though the muscles of her body had been cut straight through at the tendon. Night was falling more quickly than the snow now. He brought his face close to that of the woman, kissing her eyes and lips, sliding toward her neck and chest, then, calm, lying on her, and spreading her forsaken thighs with his knees. When he was inside her, he cried like a child, his sobbing raking his chest with the same rhythm that his thrusting battered her stomach.

The caretaker dressed nimbly. He lit a cigarette taken from a leather case, and busied himself tidying up. Before wandering the labyrinth of a hundred tiny chambers, he gave the place a last look over. His steps echoed in the large hall, like a temple invaded by a lone bivouac, a dream fulfilled and weary from the exodus, never to fold its capitals and palanquins away again. Outside, the cold seemed to have overcome the wind. The snow attached itself to branches like pollen. When the caretaker passed, icy teeth hanging from low thickets shattered with the sound of glass. A carpet of hardened leaves and snow cracked with each step like ancient parquet. At the end of the path, the pavilion loomed, circled with porous light diffusing that of the streetlamps along the edge of the road. Once or twice, the headlights of a car probed the walls, their veins of ivy redesigned by the snow.

He reached the door. The key clicked, then a puff of warm air enveloped him. In the entryway mirror, his hair was still white with crystals; he recovered ten years of age within a couple of seconds. The apartment was large but designed for a single man. Ultimately, the layout satisfied him. No one had ever crossed the threshold except for the two ward housekeepers, Hashiche and Duclos, who sometimes came to down a bottle and infest the kitchen with their composite odour of the pharmacy and a menagerie. Those two never upset his habits. They never interrogated him about his tastes, and respected his compulsions. He also took a certain pleasure in conversing with them, amused by the deference that his beautiful manners inspired in them.

The house had another inhabitant: an enormous cat who purred in concert with the stove. Content to find himself among his books and furnishings, the caretaker put his slippers on, took another cigarette and started laughing softly. At his call, the cat jumped onto his lap. He stroked the creature’s black fur with the same fascination with which he had earlier bowed to the stomach of the woman. Still, a wave of disquiet occupied him despite the hours of respite. He suddenly jumped up. The surprised animal was let fall to the floor, and dashed under an armchair.

The light! He had forgotten to turn off the light in the autopsy room. Had he not switched it off the moment he started getting dressed? Already, he was running down the path. It was no longer snowing, but brushing past the bushes as he ran thew out clouds of grey powder. He slipped several times without falling, only recovering his balance with grotesque pantomimes. Reaching the main door, he stopped to catch his breath. Everything was as usual. It wasn’t so late that he had to worry about the arrival of the groomers. Reassured, he entered the building and, electric torch in hand, went down corridors in which corpses were lined up along both sides amid the moving shadows born of the powerful beam. In the autopsy room, he took time to reflect on his terrible mistake. Ordinarily, he put in place more precautions than a retired criminal could think up. The lapse was an ominous sign, spoiling his appetite for perfection. On the bed of marble, the woman was already stiff and icy, but so beautiful in her pallor. A few hours earlier, she must have suffocated from the fire in her arteries not knowing that she would be loved again, despite her racing heart and blurring vision.

Carefully, he locked the heavy doors of the morgue. His role as caretaker wasn’t only a pretext for his mores, but, above all, an expression of his strange devotion to death and its upkeep. He set off again into the night. The hospital, which extended beyond the garden in three long buildings each of four floors, disappeared into the shadow, cut here and there by the odd light in a window, behind which went on the struggle against insomnia and the grave.

The lamp in the pavilion went out in turn. Until dawn the caretaker dreamt about the dead woman waiting for the knives of the autopsy, naked and alone.

Hubert Haddad is a Tunisian poet, playwright, short story writer and novelist.[1] He was born in Tunis in 1947. His debut collection of poems Le Charnier déductif appeared in 1967, and his first novel Un rêve de glace was published in 1974.