Like hospitals, Atlantic ports are sad. All look alike, with their doubled towns sharing docks, black buildings sliding between dual seas, wooden hovels where the elderly knit, hollow trunks. Like handsome cabs hitched to cast-iron heads, trawler deckhouses shimmer along the quays. A low-lying town sways in dirty waters; it puts up bridges and ladders in the circus-like encampment, staining the harbour. A suburb of sailboats waits elsewhere. Crowds switch and mingle; uniforms spread over the wharfs, widows cluster around baskets; equipped with floats and fishing rods, the solitary contemplate rings in the water. It was the first time he was visiting the place. Once upon a time, with the exaggeration of childhood, Élénore had described it to him as his hometown, but he was moving away from it now without regret: the ocean’s washed out stations are gaudy and blinding. Too much light, and too many eyes everywhere, too many misplaced expectations. Boats and houses clashing in the din of hoists and swing bridges.

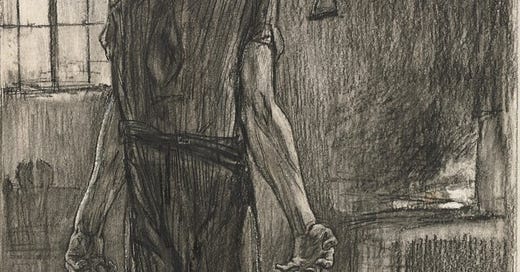

As he drove further into the fields, he worried over whether he had forgotten anything: the danger of his trek committed him not to return. Eva couldn’t be left alone; caution pressed. The provisions for a siege filled the boot. He shuddered thinking of the morning’s intoxication. When the car had almost flipped in the ditch, the distance between there and the house had seemed out of all proportion. He had had to transport Eva under the full sun. Despite his problems, and the presence of fishermen along the banks, he had calmly applied himself to the transfer. An unknown force had pushed him against the wind, the ease of his gestures underlined by the strange slowness his secret struggle had occasioned. Eva sagged between his arms, hair strewn, hands open. He walked without hesitating, with the premeditation of a dream. The immense flats, sown with handkerchiefs scattered with yew and oxen, stretched out toward the golden east. To the west, the tide beat the rhythm of his steps, like a pulse heard under a sleeping ear. Eva, white in his arms and so light she seemed to float, offered up to him her illuminated face . He was awakening from the depths of time, from between the first day and the last night. The plain was deserted but denser than centuries, the moment peopled with shadows. He was taking Eva to his childhood home, where no one died without dwelling forever. To the house of Élénore, who sang in the sea. Eva sagged between his arms, whiter than memory. When the door opened on the trembling light between oblivion and recollection, Eva held in one hand and the key in the other, the stairs creaked like the branches of a tree. Mice and things whispered in the corners; the aged furniture cracked. Step after step, he tested his gait clearly knowing he was retracing ancient dramas. Her hair spread over the banister, from which spiders fled. Everything was following the course of a dream: he took Eva to the blue room, and the house echoed beneath his footsteps with the groaning of a hull …

The car skirted the crows’ cemetery and took the side road. When the vehicle turned off, the open upstairs window immediately caught the driver’s eye. Such carelessness made him blanch: at that very moment, they would be looking for him, perhaps even with dogs and guns. Cohorts of police in burgundy uniforms coming at him like beasts to tear Eva away. Them and their kind would deliver her adorable body to the knives before burying her among roots and moles …

He shut the door of the garage with chains and bolts: concealed from the curious, the car would not come out again for a long time. There was only a little money left after his spending in town, but an entire set of top quality electronics and two months’ supplies were all he needed for his project. Each box of cans arranged in the large bedroom wardrobe was worth a day’s survival. Without counting the apple trees and sea food, he added, closing the oak doors. Eva was resting on the double bed, fully clothed, her feet bare. Her painted nails had chipped during the trip, and her creased dress was stretched along its seams. He sat close to her, and felt her throat and arms under the folds of her clothing. Eva’s body had endured reheating well enough, but he would have to hurry. Once the bed had been pulled into the middle of the room, he took off his jacket, his breath short. It was already four o’clock by his watch, and he had a day’s work ahead of him. The spools were unwound, and the lead wires stripped, resistors assembled in sequence were nailed into boxes. Amid the din of the tools, the old refrigerator from the kitchen would soon lose its cryostat, just like the large freezer stored in the laundry room. Strips of fibreglass lagging were taken down from the attic to be rehung on the ceiling and walls of the blue room. Such labour brought on a kind of drunkenness. He recalled that, from the time of his studies, everything relating to electrical DIY had interested him more so than anatomy and biochemistry combined. He liked to repair all sorts of gear brought to him by the staff, calculators, electrical appliances, thermocauterizing electrodes. Sure of himself, he barely took the precaution of cutting the current, and handled live wires as though they were bits of string. Later, at the morgue, as an experienced refrigeration specialist, he had updated the system for the cold chamber. It was a matter reconfiguring that perfect design. The closed shutters were doubled with adapted boards and fibreglass. Glue aided the nails without lessening the racket. Finally, he began on the compressors, the humming plugs, the winter’s levers, he arranged bellows for securing the mercury, circuits of refrigerating fluids between sheets of lead, lined the doors and parquet with cork and aluminium, filled every crack with cement. The blue room was unrecognisable. He was behind, but the installation had been a success: before daybreak, it was working. Once the furniture had been put back in place, he took a moment to fix a final ventilator under the box spring. Exhausted, he stretched out next to Eva.

“I’ve prepared you a bed of ice,” he whispered in her ear.

His fingers grazed her childlike forehead, slipping down her nose to her lips. He would have loved to hear that mouth speak, and reticently question it.

“A bed of ice,” he repeated. “A bed you will sleep on dreamlessly for a thousand years.”

Her curls rolled in his dirty hands. With an impatient move, her turned the body over onto its stomach. Her neck emerged between locks of hair that were brighter at the roots: he bit at it like fresh fruit. Gently, he lifted her thick hair to contemplate her fine shoulders and the spindle of her back between the shoulder blades and waist. His fingers pinched the zipper, which ran down to where her buttocks began. His throat tightened as he undid the clasp of her bra, his hands trembling over the fair skin. Removed from its satin slip, the pure lines of her body were laid out across the bed in the postures of an idle puppet. Her worthy hips shone in the lamplight in accordance with the suggestive cut of deep shadows. Crazed, with one hand he tore back the final veil wanting to mount her, but his flanks collided with the stiff angle of her thighs. In vain, he tried to enter further. Death had forever sealed her bones beneath her apparent pulchritude. He collapsed at Eva’s feet, pleading for a life impossible. Ten times more he tried to possess her corpse, turning it in every direction with frenzied gestures, biting at it, scratching it without response. A dark madness entered him. For a long time into the night, he howled in terror at being alone. Completely exhausted, he slouched down to the garage to rummage under the car seat: as quickly as possible, he returned to the bedroom, a nurse’s bag marked with a red cross under his arm. Fear peaked at seeing Eva again so calm, her big, bright eyes open amid the bed’s disorder. But he gathered his courage. In the bag, he discovered his treasure: two syringes, a twisted teaspoon, and seven or eight sachets of powder. He rolled up his sleeve, and undid his tie. The snow sizzled in the teaspoon with a little spit. A drop pearled on the erect needle then sank into its channel. He breathed, his eyes closed. The flow of the golden liquid filled every morsel of his body with a kind of serene blaze. When his eyes reopened, all fear had left him. He placed the bag under the bed and wrapped his arms around the dead woman. The awkward injection burned a little, but his whole being was breathing anew. I no longer have a body, he thought. Eva offered her sharp profile to the pearly glow of the lamp. Her beautiful breast, slightly tainted around the areola, rolled against him. Lower down, her cut wrists showed off their sweet shadows.

“I love you,” he said, in a voice that was husky, astonished by itself.

From the silence of the night rose the song of the waves. Alone with her amid the ebb and flow of the heavens and the sea, the rest of the world, far from the blue room, rejected, he felt perfectly free. Gaze fixed on the infinite, his entire being escaped in the pure contemplation of Eva.

“I will always love you,” he said again, as though he were inventing the world.

Gold ran from his eyes on his erring right hand. His voice choked in Eva’s hair.

“I will be the guardian of your bed, the good dog who licks your feet for a thousand years.”

For a long time, he dozed, slow images coming to mind. As the moon began to rise, anguish gripped him with the notion that the valets of justice were perhaps circling the house. He got up to calm his fears: only the barking of a dog answered the abyss of the open sea from the deserted countryside. The sweetness of the breeze bathed his face. Nothing but the orgies of tawny owls in the pines and the noise of the racing shrews troubled the night. He returned to the bedroom and, distractedly, opened the wardrobe. Behind a velvet curtain, Élénore’s dresses were arranged. One after another he took them down, probing his memories. Élénore in summer. Élénore in winter. Élénore in the daytime or Élénore at night! Flannel and furs slipped through his hands. Cut in the fashions of the time, they had kept their colour and their pleats. Each one had its story, its perfume. Folded at the waist, he raised a long, tightly-fitted, black silk gown to his lips, and then another, a spring dress with flowers and sails. Memories in the flow of life followed one after another, like a song without refrain: forgotten parties, grief and bitter rain under the porch of the church, sunny walks among trees which hid their laughter. Underwear as silken as flesh seemed to have been abandoned only the evening before. He selected a bodice and stockings, as well as the most beautiful dress. White with a pretty plunging neckline, Élénore had worn it for dancing of an evening or for dreaming in the verges of the waves. One night in particular, a summer’s evening of great beauty, he had come across her in that dress so white against her tanned body. The fevers of a heatwave had veiled the sunset in a mist. She had been dancing completely naked on the burning sand while he hid among the barques. Dressing again in an instant, she had launched herself toward the coast, her dress lifted to her hips, as he had thrown himself into the waves to conceal his excitement.

“I don’t remember any more,” the man said slamming the wardrobe doors.

His arms full of old adornments, he knelt before the bed. The fabric screeched over her lower back, her thighs, raised over her chest. The zip slid: Eva, as sumptuous as the large dolls that decorate department store windows, seemed as though to relax a moment before the bright lights of a ball. Her hair, loose across the sheets, was done up without braids or bands. A broach appeared on her breast, and shining hoops in her ears. Once she was ready, he grew worried about the hour: the day and its heat would not wait. Leaving her asleep, he took his tools again in hand. He still had some screws to tighten and some insulation to adapt before starting it up. When everything was in place, he carried out a final review. One faulty contact and his installation was at risk of a conflagration. He checked every centimetre of the circuits, rotors, control sticks and terminals, inductor spools: the machinery was set.

The contact lever clicked in the chamber. A steely-toned siren thrummed for a few moments, followed by the muffled rumbling of engines. The face of the former caretaker lit up: the refrigerating machine worked wonderfully! He went to watch the mercury column. The metal liquid ebbed degree after degree. Once zero was breached, the steam released by the drop in temperature turned to snow. A polar wind swirled under the effects of the rapid glaciation. Mad with joy, he ran to embrace Eva in her eternal robe. The mercury continued to drop then the thermometer exploded on the wall. A stain the colour of blood ran down to the floor. The engines hummed more beautifully, and frost now whitened the furniture and partitions. A few snowflakes were still floating. As rotating fields were suspended, between breaths of the storm, one could hear the sound of waves. The former morgue caretaker revelled like a child before the complete realisation of his dream. He danced in the blue room, calling Eva’s name. The cold gave him a strength which burned in joyful acrobatics. But his limbs gradually grew numb, a different ice freezing his veins. He wanted to walk on the beach.

Three steps separated the North Pole from the Tropics. Sweat soon soaked his shirt. He undid his collar. The air was heavy and perfumed like a living woman. He walked the length of the shingle where the ocean’s spume gathered. Eva occupied him completely, the joy of her body, a warmer thought than the slow poison in his veins. Barely had light hit the plain than the night lost a couple of stars. To the west, a quarter moon stained the horizon with anaemic twilight. Hands in his pockets, he wandered the dark sands where shells cracked. A gold tooth rolled between his fingers. “A ring for Eva,” he muttered, searching far and wide for a meaning to his words. Like that everything came crashing down: he glimpsed the house before him and raised his right hand to his lips. Everything was the colour of yesterday. A sob of fright shook him. He wanted to escape, to run! But every step brought him closer to a shattering secret. He turned back toward the nascent dawn: the portents were the same, it was the same wheel of blood! The sun burst in his head. Gripped by vertigo, he sank into a whirlpool of memory, where, unforgettable, the song of recurrence echoed.

Hubert Haddad is a Tunisian poet, playwright, short story writer and novelist.[1] He was born in Tunis in 1947. His debut collection of poems Le Charnier déductif appeared in 1967, and his first novel Un rêve de glace was published in 1974.