Rintoul lay in the wet grass, much to the consternation of the funeral goers two plots over. He looked at the sky. The rain had stopped in the afternoon, and though its chill was now seeping through the layers of his clothes, the burly evening’s clouds appeared more sulky than aggressing. He rolled onto his side to avoid the neighbour. The stone to which he turned embraced him.

His mother’s tomb was shiny, the dates sharp and crisply cut. Her name had been inlaid with gold, the marble black. It was the first time Rintoul had visited alone; the first time he’d been back since her interment. It would soon be closing time. He knew his stepfather’s visits took place mostly in the morning.

I could stay all night, he thought to himself. People sleep in worse conditions than this. He clamped the cuffs of his jacket to his wrists and wrapped it tightly around him. I guess there’ll be a security guard of some kind, though. Someone to check the homeless don’t break into the mausoleums and set up camp. He half sat up and looked back, peering over his shoulder at the mourners who remained. They were no longer paying him any attention. Their service finished, a wordless signal had gone out that sufficient time had been spent at the newly gravid plot. People had started drifting away. No doubt one of them will snitch to the warden, Rintoul thought curling back around.

He wondered to what extent grief supplied a pass for unusual behaviour. The flowers on his mother’s grave were fresh, the tombstone visibly recently installed. What other reason could someone have for choosing to lie down beside it? Any cemetery employee must have seen worse, stranger and more disconcerting displays from the clotted and wrenched bereaved. He checked his watch. He couldn’t stay much longer after all. Nothing too untoward; Veronika would be getting worried. If he’d told her in advance where he’d been planning to go, she would’ve been supportive. Not having spoken to her since leaving for work, however, the scope of her composure would be curtailed. She could be anxious at the best of times.

Rintoul listened to the air around him. Nothing moved. He could hear traffic in the distance, the roar of city life on the far side of the graveyard walls, but the sounds that reached him only served to heighten the silence into which he’d sunk. From the apartment buildings that surrounded the cemetery, he could make out the honeyed yellow lights of cosy, well-heeled interiors. Figures moved about from room to room, preparing meals, settling in for the late-autumn night, chatting with others that couldn’t be seen.

He felt neither envy nor desire. He didn’t wish to join them or hurry back to his own cosy home. He didn’t long for the smell of cooking, for warmth, or the glare of the television screen. There was no wistful tug to be held by an apartment whose dimensions slowly closed around you as shutters were shut, curtains drawn and lights turned out. None for that space in which all illumination is reduced to that between you and the one with whom you’re sleeping – the ember of yourself, for those who sleep alone. With benign remove, he took it in, imagining himself outside of time. He saw the city as a matrix of diminishing glow, each light gradually dwindling to its most discrete point. Across the city some lights would shrink to black. People are snuffing out, he thought, all over.

There were still lights inside his wife and daughter. He could pick them out of the city’s spread. He knew their flames both from their colour and the incense rising from them. He found his step-father’s, and watched as it guttered. The virus, having taken Celia, was working away on him. How could it not be? He’d barely left her side since they’d first met and hadn’t wavered a moment in her care. Rintoul had been advised to stay away, and, without a fight, he’d complied. Keeping his wife and child safe was how he’d justified it to himself.

Back on the pressed earth, the points where his elbow and hip had planted were rapidly pressing to mud. Rintoul struggled to remember the last image he had of his mother. People all looked the same in hospital beds. And worse, he thought, every face she would’ve seen in her last few weeks would’ve looked the same as well: covered in a mask of some description, reflections in goggles and visors obscuring the glint of the eyes within. What upset him most, however, was knowing that the symptoms would’ve taken her sense of smell. If I had gone, he thought, she wouldn’t have known it was me anyway, unable even to detect the animal scent of my sweat and skin. He breathed in deeply for the soil, the rain, the sky, the ending year. The night had darkened without him realising.

A man approached.

“Rintoul,” he said, sounding like a ghost, “is that you?”

Rintoul sat up. Backlit, he couldn’t make out the man’s features, but even with all the years that had passed he recognised him.

“I didn’t expect anybody to be here at this time. I didn’t think I’d be disturbing anyone.”

His father’s voice hadn’t changed.

“How did you find out?”

“Her husband called.”

“Did he tell you that he’s got it too?”

“He did. How do you rate his chances?”

“About as good as anyone’s.”

They fell quiet.

Leaning on the gravestone, Rintoul stood and straightened out his trousers. The ground had left wet patches on his clothes, as though it were a child who had cried into his folds.

“You’re not angry with me for coming here, are you?”

“No, dad. I’m not angry with you for that. You’ve got every right to mourn.”

They stood side by side on the tarmac path. From somewhere on the far side of the cemetery, they heard a whistle blow. Rintoul took his mask from his pocket and put it on. Cordonnery kept his in his hand.

“I’m surprised Luc had your number.”

“We speak from time to time. I assumed you knew. A while now. For your mother’s sake. Not that she could ever have admitted – ”

“I think it would be best if you don’t talk about mum.”

*

On the terrace of a boarded-up bistro, the landlord had set up a trestle-table from which he was selling spiced wine and beer. They’d hung fairy-lights along the awning. As Rintoul and Cordonnery approached the metro, it caught Rintoul’s eye. “Time for a drink?” he asked, nodding to the makeshift bar. The walk from the cemetery had proceeded in silence. “I do,” Cordonnery replied.

“I don’t feel much like going home yet,” Rintoul said.

“I know the feeling.”

They took their drinks to the far end of the terrace where an electric heater glowed. There were only two other customers hanging around, one smoking and laughing with the barman, the other in a black coat drinking alone. Rintoul thought he recognised him as from amongst the funeral crowd. He nodded, as though offering condolence. The man blinked absently and took a drink. As he held the wine up to his lips, Rintoul tried not to stare at his hand. Long and skeletal, his fingers cramped to a clutch around the plastic cup. The nails to which they tapered were long and pointed. The man, as he swallowed, closed his eyes.

Before taking a sip himself, Cordonnery held his drink up in salute. Rintoul looked his father over. He’d always been an unprepossessing figure, and with time his dark eyes had been drawn deeper, becoming more melancholy and interior. Other than growing a thick moustache, however, he didn’t look all that different from what Rintoul remembered. He was glad that the years hadn’t aged him more. That his facial hair and the suit he wore were so old-fashioned also comforted. Cordonnery had a timeless look that fit with Rintoul’s conflicted nostalgia. His father could have stepped from a photograph. Although with his scent of damp-wool, mulch and pipe tobacco, he could’ve just as easily emerged whole cloth from the autumn night.

“I didn’t think you’d smoke,” Rintoul said, as, having placed his cup on the pavement, Cordonnery withdrew his pipe and began to slowly stuff its bowl.

“Always have.”

“No, you didn’t.” Rintoul felt indignant. His father didn’t respond.

“I’m going to get another,” he said, emptying his beer. Cordonnery looked down, he’d barely touched his wine.

I can’t believe it’s actually him, Rintoul thought. “You know you’ve barely changed at all.”

Cordonnery shrugged. “I should have?”

*

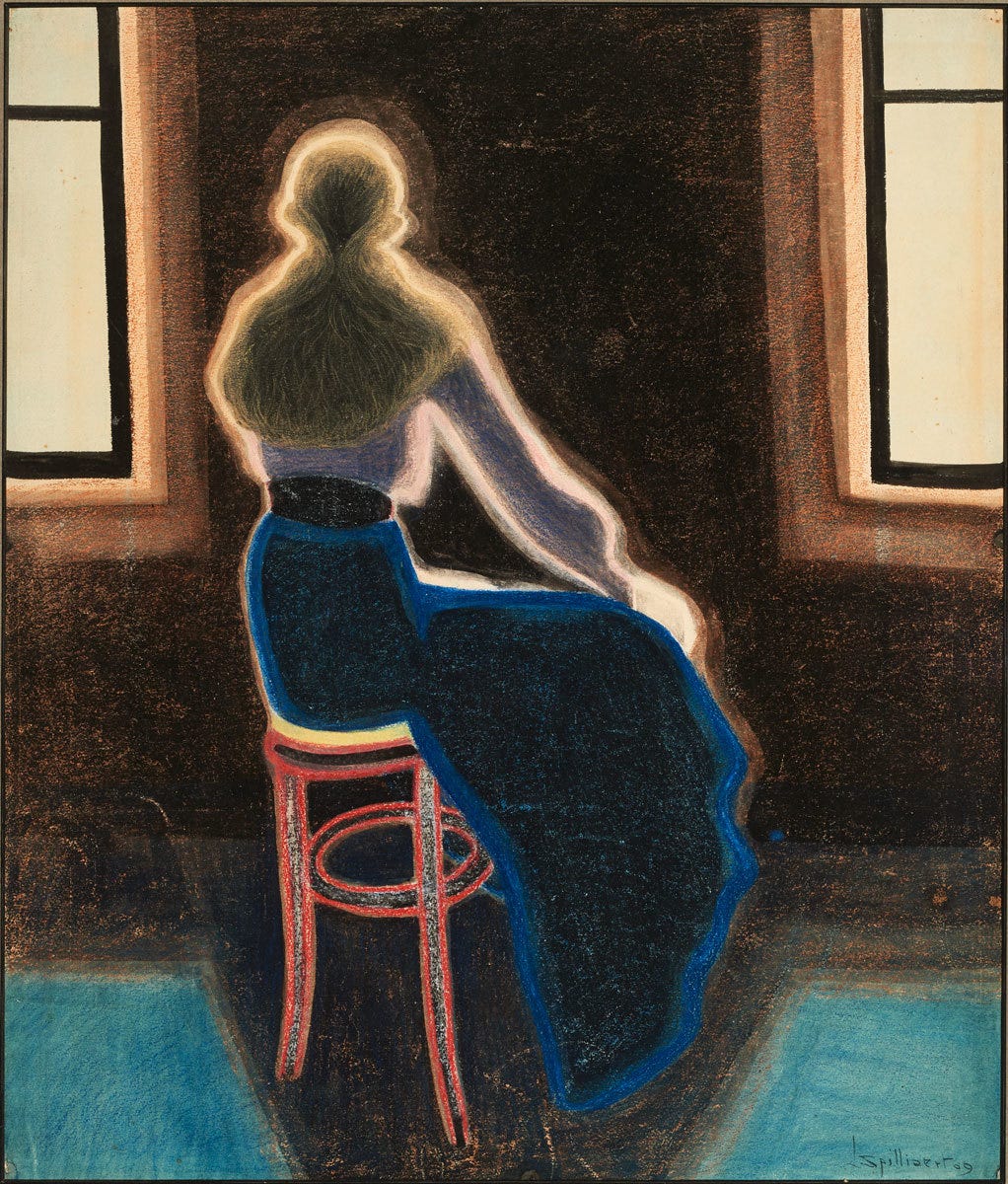

He stood still in the unlit kitchen. Framed by the doorway, he could see Veronika sat in front of the television, ringed with its light. Her long blonde hair was loosely tied, her robe cinched high around the waist. She was sitting on a dining chair, dragged out from the table into the middle of the floor. Her posture upright, braced with anticipation, her hands were placed on her spread knees, ready to react at the slightest instigation.

Expecting her to be in bed, Rintoul had shut the apartment door as quietly as he’d been able. Up the last few flights of stairs, he’d thought through every moment of his arrival. What to say if she was sat at the table, her eyes fixed on the door, how to get to the bedroom silently if she wasn’t; how to undress without disturbing her and slip under the covers; how he was going to explain himself when confronted the next morning. He was caught now in circumstances he’d not anticipated. His wife looked beautiful, untouchable, and unbearably distant. He could think of neither what to say nor do.

She glanced back.

“Oh, I didn’t hear you coming in.”

Rintoul backed off to give her room as she picked up the chair and returned it to its place at the table. “I waited up,” Veronika said.

“Anything good on?”

She kissed his cheek.

“No, no, I wasn’t really watching. My mind was wandering … Where were you? You missed curfew.”

“I don’t even know how to start to tell you.”

Veronika turned and went to switch off the television. Rintoul lost her for a moment in the dark. She flicked on the light as she came back into the kitchen.

“You found somewhere to get a drink, anyway.”

“My dad was at the cemetery.”

*

“Well, at least we know now why Celia never agreed to have him declared dead.”

Rintoul’s eyes narrowed. “Don’t talk about mum.”

Veronika folded her arms. From across the table, she could see the tears welling in her husband’s eyes. He dropped his head. His sorrow was a private, adolescent thing: filled with shame, volatile and confusing. She reached out and he ignored her hand.

“Do you want me to stay up with you or do you prefer to be alone?”

“Alone,” Rintoul said. He looked like a little boy.

“You know where I am if you need me,” she offered, and moved towards the shadows of the corridor. “And I’d drink some water if I were you.”

*

Rintoul sat at the table and bit his nails. The nail of his index finger was thick and tensile. Taking it on the tip of his tongue, he turned its point and jimmied it into the flesh between his teeth. He winced. Once pushed through, and driven deeply in, he wound it around like a crank with his tongue. It scraped and notched painfully. There was a slight taste of blood in his saliva. Supping a vacuum, he loosed the nail and worked it in again.

*

In the bedroom, Veronika tossed and turned. The conversation with Rintoul had told her nothing. He didn’t know where his father was staying, just that he’d found himself a hotel. He didn’t know for how long he’d be in town. He didn’t even know a thing of where Cordonnery had been in the twenty plus years that he’d been missing. “Of course I asked,” Rintoul had said, “here and there. Here and there.” He’d bobbed his head from side to side, mocking. She hadn’t liked seeing him so drunk. It wasn’t something she was used to. “And you didn’t push him? Aren’t you curious?” Her husband had shrugged. “What difference would it make?

“He told me that he liked to make models out of matches. It began with model aeroplanes and went from there. He’d wanted to build a hanger, he said, make scenery for the planes he’d made. And then he got more into it. He built a lighthouse, a pier and a pavilion. He’s made scale models of all kinds of famous buildings, The Royal Palace, the Arcade. That’s what he does. Hour after hour, he sits and glue matches together. Piece by insignificant piece. He’d like to make the whole city, he said, bit by bit. Build it all. And then he showed me a figure he’d made from pipe-cleaners and whittled wood. He’s going to make more, he said, everyone, the population. He’s going to make one of us all.”

She thought of the fastidious way that Rintoul cut the crusts from toast and how often she had caught him staring into space.

*

Throughout the night, as he sat at the table, Rintoul probed his mouth, seeking out tender spots to prick and torture. He was trying to see his father’s light. He couldn’t. For as far back in his life as he could remember, Cordonnery had had no light. In the place where a fire should’ve been, Rintoul saw a stone. It wasn’t imposing and nor did it express some monumental indifference or granite reserve. Cordonnery was a small grey stone, round and smooth, inert, and inoffensive. His father was a man who could fit into the pit of his hand, someone he could close his fingers around; someone to launch from a bridge or a shore into waters whose currents were the grace of forgetting. But he’d never been able to. He turned the pebble over. Across it ran a vein of quartz, breaking a like a bleak horizon. Holding it to his eye, he saw the furl of a leaden ocean. His thumb caressed the surface curve and covered the rise of the white and heatless sun. He lay it flat and trembling on his palm. Let it become a talisman.

Rintoul knew no explanations would be forth-coming and he didn’t blame Celia for not providing one. There were none he could imagine that would satisfy. He forgave her. When Luc died, there’d be no one who could offer reasons. And then Cordonnery would die as well and there’d be no one left who’d ever known.

As the point of his fingernail broke through, emerging from the gum between his two front teeth, Rintoul saw the matrices of the black city, its infinite points of light, rising on a wave. A pitch tide lifted and the waters sank, and lights expired and many more pooled on the incoming swell, and pooled again on the replacing swell and pooled once more on the swell, and pooled again on the replacing one.

He felt seasick, stood, and vomited in the sink.

*

In a fitful sleep Veronika dreamt of a cloud-banked sky. The wind beat and blustered at her cheeks but not a hair on her head was disturbed by its howling. As the heft of the weather front began to shift, a great column of black cloud rose before them. Her children were playing on the sand. Two little girls in matching bonnets, or one and her reflection in the muddy shallows.

When she lifted her eyes again, the cloud had taken the form of a woman. She towered above them, dressed in mourning, and threw back her head as though she were falling.

*

The next day, when he joined them for breakfast, Elsa asked Rintoul if he was feeling well. “You look green, daddy,” she said. Veronika, hollow-eyed herself, rubbed his shoulder as she brought his eggs. She mimed over their daughter’s head to ask if he had thrown up. Rintoul nodded.

Veronika watched him eat his breakfast.

Beside him, Elsa was scribbling furiously with her crayons. Since answering her question, Rintoul hadn’t looked up.

“What’s that Elsa’s making, dad?”

Rintoul leaned over and looked at his daughter. He turned her paper around.

Elsa looked excitedly at her mother, who nodded and smiled in return. “Go on,” she mouthed. Elsa chewed the crayon in her hand. “What is it?” Rintoul asked.

“It’s daddy under the sea,” she giggled. “That’s you and that’s a whale and that’s a sail boat.”

“And where are you and mummy?”

“We’re somewhere else!”

*

That afternoon Veronika phoned him at work.

“How’s the head?”

“It’s been better, but I’m alright. I’m sorry about last night.”

“No that’s ok. I understand.”

She asked if Rintoul had got any contact details from his dad, an address or a phone number where they could reach him.

“We should talk about taking Elsa to meet him.”

In the inside pocket of yesterday’s suit jacket, there was a napkin from the stall where they’d bought their drinks. On it, Cordonnery had written an address. Rintoul, in his state had forgotten about it.

Eyes closed, he pinched the bridge of nose and shook his head. “He didn’t tell me any stuff like that. He said he’d found a hotel, and that was it.”