“There’s a man in the garden,” Eckerlee said, tugging at the sleeve of his mother’s dressing gown. Mayerlinne looked up but otherwise ignored him. She returned her attention to that day’s number puzzle. “There’s a man in the garden.” This time she didn’t turn around. “Mum!” She dropped her paper and stared at the fireplace. “Come and see, mum. There’s someone there.”

It was rare for Eckerlee to persist this way. Most of the time, his creative side was expressed in reams of scribbled upon paper, of which Mayerlinne could make neither head nor tail, and in whispered conversations with imaginary friends as he sat in the corner of the living room, facing the wall.

Mayerlinne sighed and stood up. “Come on then.”

Eckerlee hadn’t been himself for a while. Ever since their cat, Spill, had gone missing he’d been drawing less and spending more time by himself. It was thanks to the disappearance of the cat, after all, that he’d taken to sitting on top of the washing machine in their little back porch, eyes fixed on the narrow window which looked out into the yard. He’d sat there every evening since Spill hadn’t come home. Even the closing in of winter, which had made it near impossible to see beyond his own reflection, hadn’t stopped him. I should’ve put a stop to it the moment he started turning out the lights, Mayerlinne reproached herself. What kind of mother lets her child sit like that in the dark? Still, she felt she could hardly blame him. She knew how badly he longed to see that tear of white fur drop from the wall at the far end of the garden. To go on telling him not to get his hopes up at this point seemed unkind. Better not to make too much of a fuss. She’d thought he would’ve got over it by now.

What lay beyond the garden wall was the real problem. The playing fields were more heath than grass; a scraggy patch of barren land that spread from the edges of their estate to fold into some indistinct horizon. Evenings, dotted lights could be made out in the distance, the odd hamlet or farmhouse glowing like a drifting ember over hinterlands which sloped to the high, open moors. A solitary set of goalposts betrayed abandoned municipal hopes from the time when the limeworks had been open. Other than that, the landscape gaped.

It was no surprise to Mayerlinne that a pet might go missing once it strayed beyond the garden. It was why she insisted that the boys stayed within its confines. Since moving to the village, stepping onto the field had always left her with a disconcerting feeling of exposure. Dimensions loomed. But as troubled as she was by the expanse, worse was the accompanying, uncanny sense that she was being watched. A patient and possessive eye seemed to trace across her, drawing her out from the sullen surrounds for bloodless study and consumption. The leer would drain even the solitude from her. She would find herself breathless, in a fluster, and worry that she’d get turned around, wander too far from home and never be found. The fear got worse as the days got shorter, and deepened precipitously for her boys. Spill, she’d concluded, had already succumbed.

As she followed Eckerlee through to the kitchen, Mayerlinne went down the mental list of chores that she still had to do. She felt aggrieved. That evening’s puzzle had been particularly good. Her mind had been completely absorbed, which was just about the only moment of peace she’d found her in day. There was so much she wished that she didn’t have to think about, more of the stuff all the time, and no sign of any let up. She wasn’t in the mood for Eckerlee’s messing.

She rehearsed the comforting certain to be needed, the explanations, demanding repetition, that whatever Eckerlee had imagined wasn’t able to hurt him: that it was a shadow cast by a tree or a bag caught on a branch, an odd intersection of lights which had caused the misty air to take forms that could be confused for human. It wasn’t that she minded comforting her son. Rather the problem was the transfer of disquiet. Creeping fears would hang on her every word, riding her calming speech to catch on loose threads and in the folds of her clothes. Later then, when Eckerlee was happily asleep, each phrase would re-emerge to needle; the more she’d repeated each soothing line, the louder its assailing echo.

Before her husband left, Mayerlinne had been braver. Or perhaps, she would argue with herself, I’m braver now, whereas before I was only unaware. Either way, with Owain around, she’d rarely had to confront such fears as looming figures in the shadows or intruders dropping in over the back-garden wall. That would have been his department. She’d felt secure. The world was the world, she’d repeat to herself, as she’d always been told, and life unfolds with crude sense for those without the time or resources to indulge in notions of what it all might mean. When he left them, however, the question “why?” pressed at her in ways that she’d never known before. It stalked the fringe of every thought, and paid no mind as to whether or not she had the will or means to address it. Picking at the scabs its niggling raised seemed at once to reinforce her resolve and lead her down alleyways she didn’t enjoy.

Without turning on the light, Mayerlinne walked right up to the door and put her face to the glass. Eckerlee wavered at the porch’s threshold. How the boy thought he could’ve seen anything at all amazed her. The night was thick and close, the yard as deep in shadow as she’d ever seen it. “There’s no one there, love,” she said, turning around. “There is.” She looked again. Her eyes started to adjust to the shapes she could identify, the fuzzy line of the hedge separating them from the neighbour on the left, the fence from the house on the right. The neighbour to the left had mounted floodlights on their back wall, as though to hold off the darkness of the encroaching heath, but little of that light made its way through the privet. The house to the right had been empty for years. Squinting, the line that cut the concrete path from the grass was clear enough, and far off, at the back of the garden, Mayerlinne thought she could just make out where the neat black of the wall dissected the mottled gloom of everything which lay beyond it. There definitely wasn’t anybody there.

“There’s no one, Eckle, like I said. You’re seeing things. The darkness is playing tricks on you.” He frowned. “You have to close your eyes,” he said. “Close your eyes and when you open them, he’ll come back.” Mayerlinne looked down at her son. He didn’t seem in the least bit scared. “Alright, enough’s enough. No more of it tonight. Time for bed.” Eckerlee broke out in protest as Mayerlinne ushered him back towards the hall. “Keep arguing,” his mother said, “and you can forget any chance of getting a new cat!” “Spill’s coming back. I don’t want a new cat.” “And I don’t want a spoilt brat for a son!” Eckerlee shrugged her off and stamped his feet. “Eckerlee, I swear to god, if you wake your little brother up.” They’d reached the bottom of the stairs. “You get up there now, brush your teeth and get to bed or so help me. Even if that cat does come back, he’s going straight to the shelter!” That shut Eckerlee up. Off he went. Mayerlinne sat on the bottom step. She closed her eyes. No sooner had she, then her face creased with regret. The fear that when she opened them again there’d be a stranger standing in the hall took her breath. “Don’t be daft,” she told herself, inhaling deeply. “Don’t be so bloody daft.”

*

That night Mayerlinne stood in the bathtub and brushed her teeth in the dark. She levered the frosted window up, peering out as best she could. With the added height, more of the neighbour’s light bled through. The yard was empty.

She thought about the dialogues Eckerlee carried on, chattering away to himself, to his imaginary friends. When she would ask, he never gave more information than that. “Who are you talking to?” “I’m talking to my friends.” When Cordonnery was born, she’d considered this self-sufficiency a boon, and up until recently it hadn’t given her much cause for concern. Increasingly, however, she worried about Eckerlee’s state of mind. He never spoke about his dad. He hadn’t once asked why Owain had left. He never asked to see him, if he could visit him or when he would be back. His behaviour hadn’t really changed, unlike his little brother, who had started biting his nails until they bled and more than once had wept so loudly in his sleep that it had woken her up in the middle of the night. Eckerlee had weathered these disruptions with envious, level-headed calm. Perhaps, Mayerlinne thought, now with Spill having gone as well ...

In bed she tried to parse her fears as the memory of prior bromides prickled, sweating away the comfort of her duvet. She kicked it off, thumped her pillows, sat up and rearranged herself. Over the past year, with no little resentment, she’d discovered new ways to experience time, its unfolding refracted through the strange and useless thinking to which she’d previously believed herself immune. Fears which lengthened hours thinned the timbre of the night; palpitating worries, while quickening its pace, did so while bleeding ever deeper darkness to its spread. What was worse: that there had been a man in their garden or that her son was seeing things? Wasn’t the fact he spent so much time alone, sat in the dark, the most desperate part of all? That he had no friends? That he was increasingly withdrawn? It wasn’t as though she was the only one who’d noticed. His teacher had sent a letter home. The trouble was knowing what the hell to do. Who to speak to; who might help.

When she finally did fall asleep, Mayerlinne dreamt that Spill came knocking at the door. Walking on his hind legs, he was wearing an overcoat and a battered hat. “I’m here to investigate,” he said. Lying in the garden was a little corpse under a sheet. She woke before Spill could reveal its face, not knowing which one of her children it was.

*

Eckerlee woke up the following day and went about his usual morning routine. Unlike his mother, he showed no signs of having passed a troubled night. Watching him as he ate his cereal, Mayerlinne told him that she had been up early and had gone out to look about. She’d walked all the way around the garden, the hedge, the fence, the wall, and there was no signs that anyone had broken in. Eckerlee looked at her confused. Cordonnery was oblivious. “Don’t you remember,” she said, “last night you told me that there was someone in the garden.” The boy frowned. “You dragged me away from my puzzle to go and look. Do you honestly not remember?” The boy shrugged and finished off his breakfast.

As they went to school, Mayerlinne stood and watched from the front step. Though she’d asked them to walk hand in hand, no sooner were they out the gate then Eckerlee strode on ahead, leaving his brother to struggle to catch up.

*

When Mayerlinne came in from work, the boys were both in the living room. Cordonnery was watching television; Eckerlee was sat in the corner, muttering to the wall. He was also wearing a bowler hat. “Where did that come from?” Mayerlinne asked as she bent to kiss his cheek. She expected to be told they’d had a drama class at school. “I found it on the bin at the end of the road.” Having dropped the shopping on the kitchen table, Mayerlinne dashed back into the front room. “Take it off! That’s disgusting!” Eckerlee jumped back to avoid his mother’s grasp. “I’ve been wearing it all day,” he argued. “He found it when we were walking home,” Cordonnery chipped in. “It’s filthy, Eckerlee, take it off.” Mayerlinne tried to modulate her voice not wanting the neighbours to hear her shouting. Ignoring her, Eckerlee scooted past and ran up the stairs to his room.

“Don’t cry, mummy,” Cordonnery said.

“I wasn’t going to,” she snapped.

*

“Take that off or you’re getting nothing.”

Eckerlee responded without question, taking off the bowler as he entered the kitchen and setting it down on the empty chair beside him. His little brother watched him from across the table. Relieved at the lack of pushback, Mayerlinne lightened. She asked the boys, as she always did, about their days. Eckerlee answered without much elaboration, but that wasn’t unusual. Cordonnery drew circles in the ketchup on his plate. Mayerlinne did nothing to stop him. She wanted to show Eckerlee that she was listening to him, that he had her full attention. Cordonnery sent peas spilling across the table cloth.

Only when they’d discussed their days, once she’d prised from Eckerlee what classes he’d had and what his homework for the evening was, did Mayerlinne bring up the hat again. “Don’t you like it?” Eckerlee asked. “Maybe I’ll like it a little better once we give it clean. It was left in the rubbish, Eckerlee.” “I thought it would make me look more like the man. That’s why he left it out for me.” “Who did, Eckle?” Mayerlinne asked. Eckerlee fell quiet. “I think it looks stupid,” Cordonnery announced.

Dinner over and everything cleared away, Mayerlinne took her day’s single cigarette from its packet on the mantelpiece and went to smoke on the front step. Cordonnery was in the living room playing, the TV on, and Eckerlee was sat at the kitchen table doing maths. Leaning on the door frame, she watched as the blush of the evening sun spread over the estate. With its last rays cutting the gentle furrow of the valley, the bell from Saint Mary’s started to chime. Mayerlinne breathed in and closed her eyes. She pictured the husbands returning home, trudging up the road which lead from the quarry. There had been a siren which used to sound every day before a detonation. She remembered the comfort it’d given. Even on the days when thirty seconds later she’d forgotten about it and jumped at the explosion, the recall of it was a salve. The protection it offered circled time, not only forewarning but reassuring.

When she opened her eyes again, the sky was orange and streets were empty. The bells had stopped ringing and world had fallen still. If it wasn’t for the blather from the telly, and the scrape of the chair on the kitchen floor, she would’ve felt like the only person in the world. Mayerlinne stepped out to face the sunset. Up towards the far end of the cul-de-sac, she saw a woman she didn’t recognise. She emerged from the passage leading from the playing fields and walked out into the middle of the road. Mayerlinne held her arm to her forehead to shield her eyes from the glare. It was strange to see anyone out at this time, especially someone she didn’t know. The woman stopped and turned. In the fierce light, Mayerlinne couldn’t make out much. There was something odd and unshapen about the clothes the woman wore. Mayerlinne felt like calling out. Her voice strangled. The dark pits of the woman’s eyes were locked in her direction. She seemed to be grinning. Butt burning low and brushing her knuckle, Mayerlinne winced. She dropped her cigarette and blew on her hand. A mark was already beginning to show. When she looked up again, the woman was gone.

The evening died, the sky ash and chill as the sun stubbed out beyond the rolling moorland. Mayerlinne shivered and went inside. Usually when she came back from her daily cigarette, Cordonnery would be curled up on the sofa, waiting to be taken up to bed, and Eckerlee, if his homework was done, would be scribbling away in his illegible notepad. Either that or he’d have joined his brother watching the TV. When she went into the living room, however, neither of the boys were there.

She turned off the television and returned her lighter to its place on top of the box of cigarettes hidden behind the mantel clock. She noticed its second hand wasn’t moving. How long has it been stopped? she thought. She wondered why she hadn’t noticed it before.

Turning back from the fireplace, Cordonnery was standing in the doorway. “What’s up coconut? Where’s you’ brother?” “He’s not in the kitchen,” Cordonnery replied.

Mayerlinne moved past her youngest and into the kitchen. Eckerlee was gone. His homework was still spread out across the table. The bowler hat was no longer on the chair. She panicked. Running into the hall, Mayerlinne called her son’s name. She mounted the stairs two at a time. The boys’ bedroom was empty. She checked under the bunk-beds and in the wardrobe. The bathroom was empty and her bedroom too.

At the bottom of the stairs, Cordonnery was whimpering. “Don’t cry, coconut. Don’t worry, it’ll be OK.” She sank to sitting on the steps and hugged her son. “Sorry, I over reacted, but I’m alright. I know he’s here somewhere.” She wiped the tears from his cheeks. “Don’t be upset honey, don’t be upset.” “He’s out in the garden,” Cordonnery said.

Reaching the backdoor, Mayerlinne found it locked. She could see Eckerlee in the yard through the window. “Where did he get the overcoat?” Cordonnery was at her feet. He was weeping. “Baby, go and sit under the kitchen table and don’t come out again until I tell you that you can.” Cordonnery backed away. Mayerlinne hammered on the window. “Eckerlee! Who locked the door?”

Who could have locked it was all that was running through her head. She stepped back and set her shoulder to it.

*

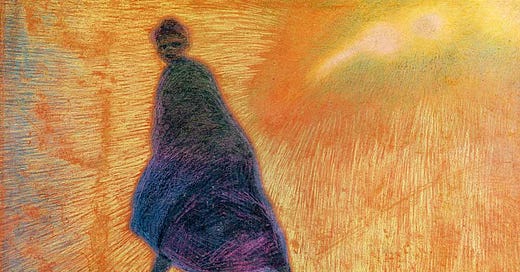

Eckerlee’s coat reached down to the ground. Its hem was picking up the damp of the night and brushing down the grass without making a sound. He would grow into it, he’d been assured. Somewhere, someone was calling his name. He didn’t turn around.

*

Mayerlinne ran down the garden and threw herself onto her son. She put her arms around him and tackled him to the floor. The hat fell from his head and rolled. When she managed to get back up to her knees, the overcoat in Mayerlinne’s hands was empty, just a bundle of old cloth with an unfamiliar smell. Feeling nothing there, she howled.

Under the kitchen table, Cordonnery bit his nails.