Eyes closed, Cordonnery stood over the washbasin and spat a welt of toothpaste against the porcelain. As he’d done twice a day for as long as he could remember, on opening his eyes again he focused on the splatter and tried to make out a shape in the lather. Plucked fowl; trussed and ready for the oven. He contemplated the significance of this as he rinsed his brush. Sunday lunch was the first thought that came to mind. A roast. With a thumb he smudged a fleck of foam from the mirror. He pawed at the bags under his eyes, his cheek’s flabby mottle not so far from chicken skin. You’ve been spending too much time inside.

Sunday lunch: the smells and steam, the abundance. Was it nostalgia he was feeling? He heard the scrape of a wooden spoon against the bottom of the pan as his mother added cornflower to the meat’s drippings. Is this nostalgia? He hadn’t thought about his mother in years, even less so of her cooking. Celia had been a good cook but had rarely done roasts. They weren’t quite the thing that they’d been back home, all the trimmings and whatnot. He couldn’t recall the last time he’d had one. Not like his mother used to make. He tugged on the cord and the shaving light went out.

In bed, as per his habit, Cordonnery took his diary from the cabinet and jotted down that evening’s image: plucked bird, raw, ready for the oven (Sunday roast). That morning’s brush had left him, according to his scribble, the form of a birthmark. And not just any birthmark. Specifically, it had reminded him of a boy he’d known at school, referred to by everyone as Stubby Black Stumps due to the rotten state of his teeth. Stubby Black Stumps, Stubby Stumps for short, had had a birthmark down the side of his face, a jagged crook which started at the temple and dripped all down his cheek. “Shat on by the birthmark bird,” the boys on the estate had used to shout when he wasn’t being picked on for the shambles of his mouth. Cordonnery would thank his lucky stars that there was someone in his class to take attention off of him, especially once Eckerlee disappeared, what with all the rumours going around.

Stubby Stumps, someone else I haven’t thought about in years …

Curious, he remarked to himself, that both the evening and morning’s spits have gone right back to home. Running a quick review of his day, Cordonnery could see no reason why that would be. Nor, going further, could he find much that resonated with how he’d filled the rest of his week, most of which he’d spent gluing matches together for a model of the basilica.

He put his diary back, turned out the lamp and turned in. Though he wasn’t awake long, for as long as he was he lay in the half-light, curtains open, blinds not drawn, and thought about the house on the old estate. He remembered the pattern on the lino, the shuffle of his mother’s feet in slippers as he watched her from under the kitchen table. He thought about the cigarette smell of her hair as she carried him up the stairs to the bed. And he thought about the room that he’d shared with his brother; the view from their window of the playing fields out back, and how, on certain nights when he crawled from his bunk, he could make out the meetings of costumed figures who gathered when the moon was full.

*

It wasn’t unusual for months to pass without Rintoul speaking to Cordonnery. Life, since his reappearance, had quickly fallen back into the rhythms it’d had during his absence. When only weeks after Celia’s death, Luc had fallen victim to the virus as well, that Cordonnery was back seemed of little relevance or comfort.

Cordonnery responded to what overtures the family had made with benign absent-mindedness. He would arrive late for lunches and dinners, was found knocking at the door of the wrong apartment, and consistently called Veronika “Yonne”. He’d forget his granddaughter’s name entirely. These failures of memory, along with a habit of wandering off, had Rintoul convinced he was losing his mind. But following medical check-ups, to which Cordonnery consented without complaint, the GP had reported him to be in as good a condition as any man his age could hope. A fact, he’d added, made all the more remarkable, by the twenty-plus year lapse in his medical records. “Sea air,” Cordonnery had responded, tapping his nose and winking at his son.

Other than the odd, obscure reference such as that, no further explanation of his whereabouts in the interim was ever offered. Rintoul had given up expecting anything from the man who had come back. For the most part, it no longer caused resentment. He’d impressed Veronika with his even keel and had even managed to enjoy, more often than not, the interactions his father was capable of. “I just hope,” he’d tell his wife, “that he’ll be a better grandfather than he was a dad.”

It was that which had brought Rintoul to his door. He knocked a second time. Having tried calling and sending texts, other than a letter, there was nothing to do but turn up unannounced. He’d not been to his father’s apartment since he’d moved out of the hotel. Despite all the faff, though, Rintoul’s rap was jolly and excited. He knocked again. The baby was due any day now and he wanted to make sure Cordonnery knew before the little boy arrived.

After a final knock, and an accompanying shout, Rintoul gave up. He considered slipping a note under the door, but, though finding a receipt from lunch on which to write, had no pen. His pushed his finger against the doorframe, as though pressing on an imaginary bell, and scratched a notch with his fingernail. “I was here,” he said.

Outside on the street, Rintoul stopped. Why let him get away with it? he thought. Why have I always let him get away with it? He stepped out into the road to look up at the third floor, one of whose windows looked out from his dad’s flat. He wasn’t sure exactly which was which. The tenement loomed. Every window in the building was unlit or boarded up. The entire street, never mind the apartments themselves, seemed abandoned. The virus had ripped through neighbourhoods like this, quarters where there had been no space to isolate or distance. Every single shop was shut; every second streetlight didn’t seem to work. The incoming evening pushed a fog up the street. Up from the river, Rintoul thought, or along it. He struggled to remember from which direction he’d come, which way it was to a station whose train would take him home. This part of the city was unfamiliar.

He toyed with the key fob in his pocket. When he’d been clearing through his stepfather’s belongings, he’d found, in a box in a drawer in his desk, a key with a thin, blue plastic tag, on which was written C. He’d attached it to his own set of keys without entirely knowing why. He hadn’t, at the time, connected it to Cordonnery, but a key kept safe had seemed daft to throw away, especially when someone had gone to the trouble of labelling it. It was only later, when dealing with Luc’s papers and estate, that Rintoul had discovered it was him who had signed the lease on Cordonnery’s flat. Since then, he’d forgotten that he had it.

Rintoul re-entered the building, and set off up the stairs.

*

Cordonnery’s practice of looking for shapes in spat toothpaste had no real purpose. It’d begun by chance one morning when he’d noticed the form of a galloping horse in what slid towards the plughole. No sooner was he dressed, then he’d gone out to buy a diary so he could make a note of it. Whether or not his intention had been to remember it for a particular reason, he could no longer recall. Long since before coming back to the city, reading abstractions had been a habit. He looked for patterns in everything he saw: clouds, of course, the form of shrubs and the branches of trees, coffee grounds, condiments and spillages of every kind. With the emergence of the toothpaste horse, the habit hardened into ritual.

Being neither a spiritual nor superstitious man, however, Cordonnery took no message from the shapes he found. He didn’t attach any great significance to the days when the image was especially clear or seemed portentous, when he could make out a skull, say, a heart or a phallus. On the days he forgot to brush his teeth, missing the routine didn’t bother him at all.

Nevertheless, he found it useful. He’d concluded at some unknown juncture in the past, that though whatever he picked out had no weight in the prognostic or mystical sense, reactions to the splatter could provide useful insights into a mind which was so often a stranger to itself. If there were days he saw a phallus, it suggested, his awareness of it notwithstanding, that Cordonnery had sex on the brain, something he could then decide to address when the opportunity presented itself. A skull, and perhaps, at some level, he was thinking about death. A heart and he might be concerned about his health, feeling gripes or palpitations, tightness of the chest; perhaps thinking of Celia, perhaps having dreamt of Luce.

It was rare for him to ever look back at what he’d seen on previous days. Occasionally, at the end of the month or on dates that seemed significant, he would be tempted to scan back. Mostly, however, if was enough to contrast quickly what he’d seen in the morning against what he saw that night. Sometimes a logic was suggested, but on most occasions not. Images from the day before were forgotten with the ease of old horoscopes. He wasn’t on the look out for connections or for trends, and never attempted to string together what he saw or cinch them to a narrative thread.

It was partly for that reason that he was so taken aback when, reopening his eyes in the midst of his morning routine, he saw, clear and unambiguous in the foam, the word run. He leant in closer. He blinked and rubbed the sleep from his eyes, toothbrush still clamped in his fingers. No doubt about it: run, in lower case cursive.

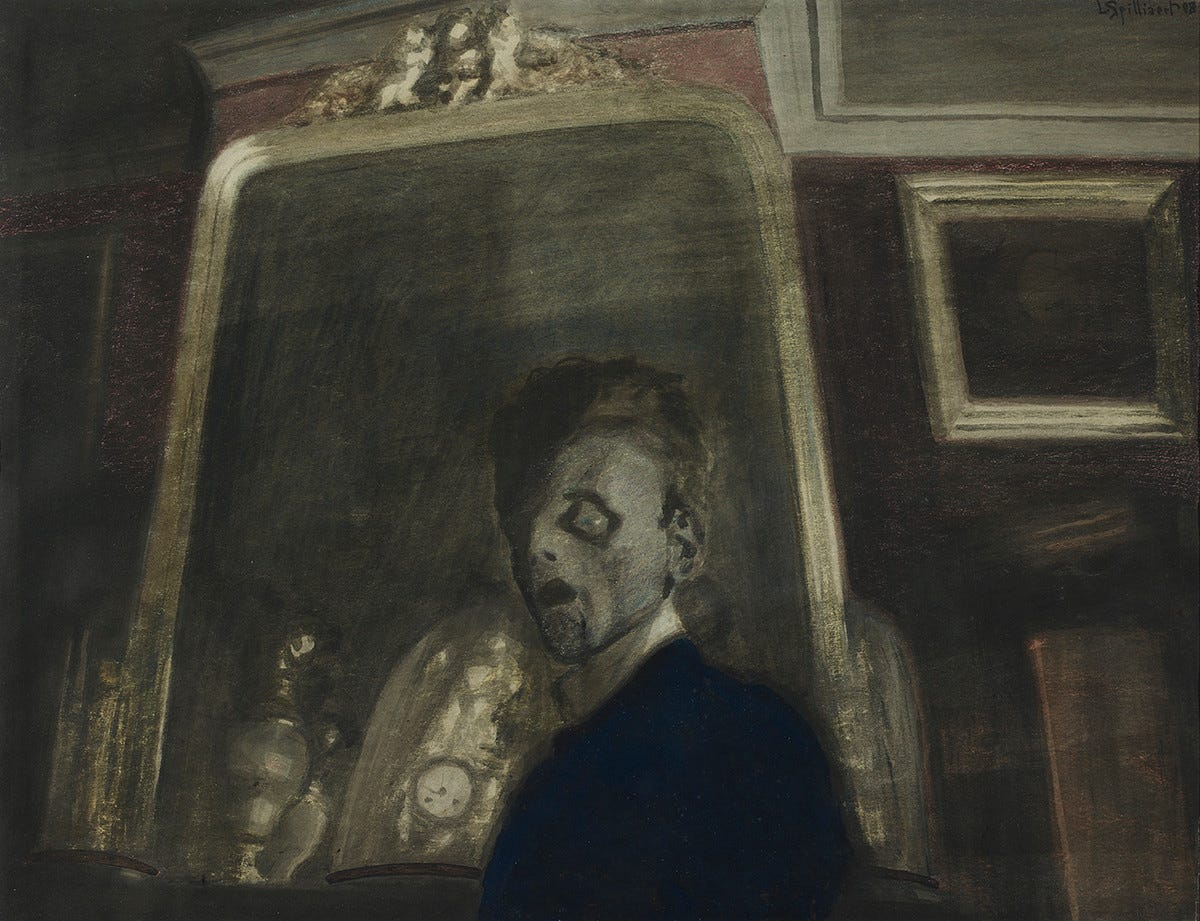

Straightening up, Cordonnery couldn’t look himself in the eye. The reflection had him pinched and gaunt, pale and almost ghostly despite the warm glow of the low watt bulb. The eye-embedded black of his facial structure showed; his hair was mussed from bed and standing on end. He kept his chin raised and looked away. Shadows drained the hollows of his cheeks and he buried his head in his hands. He pressed his fingers into his eyes. Keeping them closed he turned on the tap to splash his face, realising too late that the message would be washed away. He turned off the tap again: ruin the toothpaste now seemed to say.

Cordonnery sat on the edge of the bath and ran the water in the sink. He watched the slow ooze of the diluted foam as it edged towards the plughole. Run, he thought. But where’s left to go?

*

The apartment had clearly been empty for some time. Weeks of junk mail were wedged under the door as Rintoul edged it open, knocking and calling. The air smelt of an earlier time of year, when the days were warm enough that you might leave a window open. Trapped since, however, it’d staled, marred by the drifting dust and the gradual succumbing of expiring flies. Everywhere was spotless and everywhere was soiled. He ran a finger over the countertop, brushing off the smut with the roll of his thumb. He called out again. Even with the state that he found the place in, he wouldn’t have been surprised to find his father going ever on in his mute and sullen way of being.

Despite the staleness of the place, there were no fetid odours. There was no sign of a break-in, violence, accident or disturbance. The longer he listened to the silence, though, the more convinced Rintoul became that he was going to find his father dead.

As he passed from the kitchenette into the living room, Rintoul saw the mobile phone that he’d bought for Cordonnery lying on the coffee table. Its battery had expired. Before continuing through the apartment, he went to plug it into the charger which was hanging off the breakfast bar. As he did, he tripped on an empty cat bowl. He picked it up. It was red and plastic and completely clean. When he held it closer, it looked brand new. It smelt like it’d never been used.

Moving further into the apartment, Rintoul saw the light in the bathroom was on. He put his head around the door, half-expecting to see a body in the tub. It was empty. The shaving light above the cabinet flickered on and off. The bedroom was the only room left to look in on.

Rintoul held his breath. He pulled his mask, which he’d taken off when he’d first reached his father’s door, back over his mouth. That Cordonnery had come down with the virus was as likely now as anything else. He knocked softly, bracing himself for the sight of his dad’s blue foot sticking out from under the duvet. The bedroom was in darkness, the curtains still drawn. Cordonnery wasn’t there.

With the lights on, Rintoul could see that, much the same as the rest of the apartment, the room was in good, undisturbed condition. The bed had been hurriedly made and a single door of the wardrobe was gaping, but other than that there was nothing out of place. Though the window was closed, there was no smell Rintoul could identify, not even the residual must that he’d known as his dad’s at depths beyond instinctive. Rintoul took his phone from his pocket and, ignoring the missed calls, wrote a text: Strange questions, has my dad been in touch? He put his phone back in his pocket before Veronika could answer and sat down on the bed.

It occurred to him that he could move in. That he could take up residence, sweating his own odours into the linens, pressing his own lull into the mattress, expending the years that were left of his life. “I could even get a cat,” he said, aloud, and gazed at the wall as he thought what he would call it.

Rintoul sat for a while and listened to the night; listened to the building, listened to the city. He could hear life echoing in the distance, water flowing through the pipes, a train, solitary footsteps down on the street. He went to the window and peered out. A gangling drunk was stalking up the road, climbing the wet rungs of reflection as streetlights slicked across the pavement. Rintoul tracked him as he moved, his rhythms odd, jerky and languorous, harried and floating. The man’s shadow stretched the whole length of the street. If I rubbed my eyes, Rintoul thought, would he still be there when I opened them again?

Returning to the bed, Rintoul idly opened the drawer of the bedside cabinet. Inside was an empty photo frame and Cordonnery’s diary. A pile of fingernails was gathered in a corner. Rintoul picked up the frame and turned it over. He recognised it as a gift from Elsa. The photo of the family he’d helped her close inside it was gone. He caught a brief glimpse of his reflection in the glass. “Seems about right.”

Taking out the diary, he read back over a couple of entries:

20th

AM: Stubby Stub’s birthmark

PM: Plucked bird, raw, ready for the oven (Sunday roast)

19th

AM: Paint splatter

PM: Bird shit

18th

AM: Runner crossing the finishing line, arms in the air

PM: Cigar left smoking in an ashtray (plug hole)

17th

AM: A woman’s pubic bush

PM: Cowpat (round)

16th

AM: Archipelago

PM: Germ/ bacteria / virus molecule (molecule?)

Rintoul shut the book and left it on his father’s pillow. He stood and walked back to the living room. Charged, he turned on Cordonnery’s phone. As soon as he did, however, he realised he’d need a pin code that he didn’t have. He tried 1234, and when that failed 0000. With only one chance left to get it right, he decided to check in his dad’s diary to see if he’d written it down. There was a list of numbers on the flysheet, but nothing to identify them and none four digits long. Rintoul couldn’t help but notice that his number wasn’t listed.

He read a few more entries from the start of the year:

1st

AM: Firework

PM: Bloodsplatter

2nd

AM: Comet, tail arcing out behind it

PM: Eye socket

3rd

AM: Bird shit

PM: Jism

Rintoul gave up.

Standing in front of the bathroom mirror, he looked at his reflection. The shadows of his eyes flickered as the shaving light blinked on and off. It’s dying light cast a pall, sallowing his skin. He pushed back his hair and it stood on end. His hairline was the same as his father’s. He couldn’t deny the resemblance. “I’m going to be a dad again,” Rintoul said. “And you’re going to be a grandfather for a second time.” He held eye contact. I wonder, he thought, if I broke this mirror with my forehead, would I find you on the other side? Rather than butt, though, he let his forehead rest against it, its chill immediately soothing. Rintoul’s breath misted up the glass.

When he opened his eyes, he saw that the sink was dirty. A crust of toothpaste had dried hard onto the porcelain. He stared at it uncomprehendingly, and imagined his father in the very same spot, stood in his underwear, toothbrush in hand.

Rintoul’s phone rang in his pocket. It was Veronika. “Is everything alright?” she asked, before he could get out a greeting.

“Oh yeah, I came to see dad.”

“At his apartment?”

“Yeah,”

“And that’s why you texted me?”

“Yeah, yeah, well, I was curious, you know. I was coming to tell him the good news.”

“Nice! And how did he take it?”

“He was delighted. Over the moon, really. Exciting, was what he said. ‘How exciting.’ He’s excited to be a granddad.”

“That’s lovely.”

“Yeah, well, you know what he’s like. But yeah. Listen –”

At the other end of the line, Veronika played with the hem of her nightgown.

“I’m not going to get back before the curfew, so I’m going to stay here. Tomorrow we might go to the graveyard. I was thinking about telling Luc and mum.”

“Oh, I thought you’d already told them.”

“I did, but I feel like telling them again.”