I woke up with Collarbone curled in my lap. We were alone again. I could, however, hear breathing from the corridor, the creak of weight shifting from foot to foot. At the end of the bed, the shape of where he’d sat could still be made out in the ruffle of the covers.

If not for the cat, I would’ve immediately got up and gone out into the hall, but I didn’t want to wake it yet. I was enjoying the vibration of its purring and the faintly oily touch left on my fingers as I petted. I picked stray hairs from my lapel and trousers, and sank into the rhythms of its breath.

Quite the night, I thought, though it was impossible to know if it was even now the night itself. Perhaps a day, or days, had passed since I’d first entered the hotel. I heard my stomach growl. Collarbone flexed. The movements in the hall had calmed. The breathing was still audible.

Cooing at the cat, I repeated its name, holding on the first syllable and the third. I whispered “pss pss pss,” as my hand whorled it spine, and scratched between its ears, feeling its pelt shift on the shell of its skull. By sliding forward in my seat, I was able to prise my legs up more comfortably. Collarbone pooled in my groin and tensed. I felt a claw poking through the fibre of my slacks, plucking at threads like an untaught finger at the strings of a violin. A tooth pressed painfully into my flesh. I yelped. Clamping it by the heckles, I tossed the cat in the direction of the bed. They were my good trousers, after all.

It landed comfortably enough on the duvet, though, clearly displeased, half pounced, half bounded off the bed and scarpered for the door. Standing, I brushed off my legs and rose up on tippy-toes, reaching out my arms. I stretched out to the finger nails and opened my mouth in an exaggerated yawn; either that or a roar. Soundless the two are indistinguishable. Or, at least, I assume they are. My eyes were screwed up tight throughout.

Before doing anything else, I decided to take a quick peek out the window. My hope was that it would either provide me with an idea of the time or else some hint of where I was. I knew that I was in The Beauportail. I knew that I wasn’t alone. But I had no idea of how I’d got there, and even less how I’d find my way home.

Opening the curtains told me little. I was higher up than I’d imagined, high enough to be able to see the sky without craning my neck, but the view was onto an interior courtyard, looking into the very heart of the building. The hotel, apparently, took up the whole block. Dark, gormless glazing, uniform and multiplying, returned my eye on every side and floor. I opened the window, surprised to find I was able to do so. It’d been years since I’d last been in a hotel, but I was under the impression that windows generally couldn’t be opened in rooms whose height was considered fatal.

I sniffed the winter air; it smelt familiar and yet mineral in a way I was unaccustomed to. It was as though being trapped there in the hotel’s interior had shielded it from the city’s smog. I took in deep breaths, ravenous, suddenly, for the night, craving its bite and ice like cleanse. It burnt like fresh water, like grain alcohol, through the settled mug of my torpor.

Above me a fug of yellow cloud was trapping bile light. It plumed in a band which streaked across the sky, holding at bay an indigo night . How strange it was to see it all so clear, to see it all so blue. Beyond the city’s eerie glow, a rich and supple starfield spread, studded with a scatter of discrete white lights: the stars themselves. Here of all places! I’d never felt so enamoured with where I’d lived. Could it be that in all those years I’d been missing out by simply not lifting my eyes at the right time, in the moments revelation was coming about?

I heard a cough from the corridor. Collarbone had come back and was dallying around the threshold. I whispered “pss pss pss” again, and that it didn’t trot over told me it was time for moving on. A regret, but I felt I had no choice. Hadn’t it brought me to this view after all? I owed the cat a little faith. Shutting the window, I followed it out, just like a kitten or a scavenger might.

Our companion had already gone.

*

Following the cat brought back memories of how my night had passed. I tried to reconstruct the voices I’d heard but could no longer hear their echo in my head. I felt I’d lost the skills that had once singled me out, my canny ear, pitch perfect tone; my ability to hear a melody once, play it back, riff on it and make it my own. I focused in on the sound of Collarbone’s footfalls, pushing my concentration to its limits. I can’t be certain what I heard as it placed its paws, but I heard something. Or perhaps I only imagined that I did. Either way, in no time at all, we were stepping in synch. I began to chat.

“Stars, Collarbone. Stars and clear skies. I couldn’t tell you the last time I saw the like … Well? What do you make of it all?” The sound of my voice arrived as relief. Collarbone, however, didn’t react, not as much as pausing or looking back.

“I trust you’ll be more forthcoming when it’s time for me to go. You’re the one who dragged me here after all, led me the whole way. Isn’t that so, Collarbone? I hope you’ve some idea of which way will take me home … “Home,” I said, but you know what I mean. I hope you’ll point me in the right direction at least. Scuppered if you don’t … What’s got your tongue? Little joke. Ignore me all you like. To be aloof is no solution to a gripe, I’ve learned that much. Like life, I’ll mither you out of it yet.”

The corridor that Collarbone had taken me to was significantly different to those we’d walked so far. Gone was the carpet; gone was the wainscoting and the dusty velour of the paper on the walls. The halls instead were lined with tile and painted in two-tone washes of grey, the bottom half slightly darker than the top. The whole length of the corridor was marked with scuffs and stains, the paint was cracked and peeling off. Unlike before, the doors we passed were more tightly packed, opening, I imagined, onto much smaller rooms, cubbies, supply closets or the like.

The cold there was of a different order too, not simply the discomfort of an unheated room. The walls felt damp and slick to touch; the chill that of a cave or tunnel. It was as though the stairs we’d climbed were not, in fact, ascending but had been leading us deeper into warrens underground. We rounded another flight of stairs. The steps were of worn and weathered wood, trodden hard and climbed without creak or groan, as pale as bone and as unforgiving. My feet began to ache.

The bannister clanked ominously under my hand as I hauled myself around the spiral. Its rods vibrated all the way down. Looking off from my landing, the stairwell gaped. It looked like the socket of a skull. I was beset by sudden vertigo. The cat walked on. Gripping the handrail, I tried to think back to when we’d made the transition, passing from the hotel’s front-of-house into the bare behind-the-scenes. If I could place when that had happened, perhaps I’d know if we were headed up or going down. I sniped bitterly at Collarbone and coughed. I was sweating despite the cavernal air, an ooze of wet around my jacket collar, though it was doing nothing to warm me up. It was only then I realized I’d misplaced my overcoat.

*

As I got to the final flight of stairs, Collarbone was waiting for me on the top step. It licked a paw, looking mightily pleased with itself. And so satisfied was it, in fact, that it allowed me to give its chin a chuck as I pushed on to the landing.

We’d reached the very top of the building.

The corridor forked in both directions, but before making my choice, I went to the window and looked out.

Weather front still holding off the city’s phlegm, I caught a glimpse of the sky again. It rolled towards an endless that took away my breath. Swept out by its blue, I rose into its black, scaling the umbra of the ever distant to find myself beyond that darkness, cast into some deeper pitch. I was lost there, something semi-permanent; the crux of a desire that it was something to exist. Let go. Fell back. Fell in amongst the silhouettes of chimneystacks and sloping roofs, mismatches of bevel, vault and mansard, the skylights, the aerials, the fire escapes and vents; dissections of the night’s again blue, dark blue, own blue, jaundiced-edged with that which promised, with a change of wind, to shunt off and leave us opened out, prone to a dispersal in the antenatal blank, in the all clear, luminous and infinite. I’ll stay here, I thought. Paint myself into a shade, into a shadow. Ball. Wrap. Curl beneath some overhang, waiting for the light like that, to see no other light.

Collarbone leapt on the window ledge and lapped the dribble from my jowl. There was still one corridor to go. Off it went. I decided not to follow.

By the time I looked back to the window, the light had changed.

I sighed.

How thin the night.

I turned away.

Instead of going after Collarbone, though, I walked in the opposite direction. As I shuffled along, I passed door after door, all of them numbered but showing no sequence. Lowering my head, I tracked the corridor around. I walked until I found myself back on the landing. I went to the window to see if it would open. Now, at the far edges of the sky, a white and heatless dawn had broken.

Collarbone re-appeared. This time I went along.

It took me down a branch off the hallway that I must have missed as I’d made my way around. After this there was no more to the hotel. The corridor closed in a dead end, a window set high up in the wall, backlit, like an abandoned crucifix, with the radiant pall of horizonless morning. There was nowhere left to go.

In the last of the rooms, the door was open and a light was on. Collarbone went and sat before it. It had shown me as much as it was going to show. I heard a voice from inside the room, but couldn’t make out a word that was spoken. Collarbone, however, immediately got up and trotted into the glow. I realised I’d had its name all wrong. What had I been thinking anyway, giving the stray a name? That I was going to adopt it? Take it home? It was gone now, either way. The door of the last lit room swung closed. A key turned in the lock.

Now there was only my breathing and the sound of my heartbeat in the gloom. I couldn’t help but hum a sonata with played over its tick; an old trick I’d learnt for staying calm. It’s all still there inside of you, a voice declared. I considered the timelessness of tempo as I drummed my fingers on my lapel. Inveterate; inveterate, after all. My left arm twitched with emptiness. “Moths,” I said, turning from the window, for the comfort of hearing my voice aloud. “Aren’t we only moths.” I fluttered my hand down.

As I walked the corridor back, I clocked the numbers on the doors, looking for one which augured well. I searched for my lucky number, my date of birth, that of a bus line which had, for a time, taken me from my door to that of a beloved. Coming across none of those, I freed my thinking. I courted fractions, multiples, patterns, time signatures, anything with some degree of link, no matter how tenuous, to what I could call meaning. Finally, finding nothing adequate, I plumped for the one which the music of saying I found the most delightful.

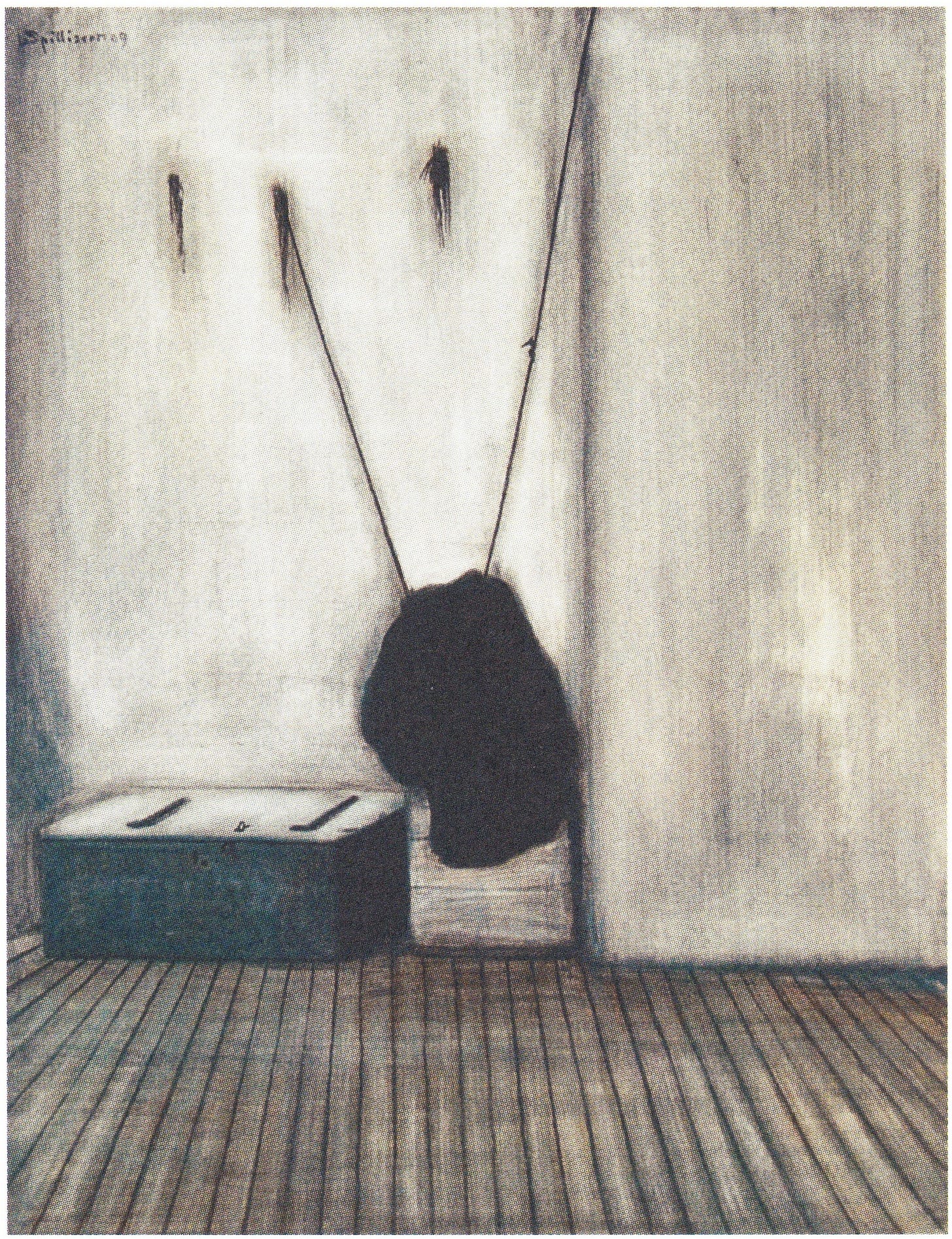

Addressing myself to the door, I knocked, only in its echo cottoning to my absurd propriety. The door edged open from the rap of my knuckle. Inside, ink black, I fumbled up the wall, finding a light switch in more or less the place one would expect to find one, if perhaps not a little higher up than my reflexes were accustomed. The room was empty, the walls off-white, their condition no better than those in the hall. I turned as I noticed a length of rope; it was strung from the corner to a mounted hook. Across it, pulling it tense to its centre, a figure slumped. My stomach turned. What remains had I been led to find? And what was this style of garrotting? I edged forwards, barely lifting my feet from the floor.

On closer inspection, what I’d mistaken for a person turned out to be nothing more than an overcoat slung over the rope. Though no longer feeling quite the chill I had, I lifted it off, wanting to slip into it and warm myself up. It fit perfectly. I checked the pockets, my hand emerging from the inside breast with a receipt from what appeared to have been quite the feast of a dinner. There was something written on the back which I couldn’t understand, though its scrawl looked familiar. “What a turn up,” I voiced. Our companion must have taken it from me and prepared the room for my arrival. Considerate, I thought, and stretched out my arms. The sleeves seemed to have shrunk since I’d last worn it. My wrists were jutting, looking terribly thin.

In the corridor, the lights went out with a thunk, which spoke to an automatic timer. I’d barely been aware of their illumination, and less so of any mechanical whirr, but now it was gone the absence thrummed. I thought back through every step I’d taken through the building, every threshold that we’d passed which had brooked no return. And then, of course, there were the barriers that I’d crossed unawares. But I wasn’t afraid. For all my natter with Collarbone, I’d known that I was never going home.

I went to shut the door. On the back of it an old bowler hat was hanging.

The room mine, I took a breath and made to settle in. There was a skylight which I hadn’t noticed at first, the pane of glass so caked in grime that not a splinter of daylight was getting through. Other than the rope, however, now slack and garlanded up the wall, there was nothing in the room but a travelling trunk.

That the trunk held my viola was quite the surprise. I was overjoyed. In a state of great excitement, I sat cross-legged in the middle of the floor and took out its case. I felt a yearning to play which I’d not known in longer than I could even say. My mind raced through the pieces I wanted to perform, to hear, to feel vibrating through me. Their every note was present in the echo of my ear as my shaking fingers scrabbled and my nails scraped the clasps.

What a let-down then it was to find, when I opened up the box, that thought my instrument was inside, it had no strings. I sawed the bow up and down regardless, a mime; my jutting arm spurring back and forth in canters of melody long since silenced. The stray and snapping horsehairs draped across my thigh. Swaying and sluicing in the crook of my groin, they furled like seaweed in a tide.

“There’s a cat out there,” a voice made itself heard, “down the hall out there, strutting around, all full of guts.” That made me smile. I thought about the butchery of cats and of horses. I thought about the seaside. I thought of every wide and closed horizon that I’d ever known. I thought about the sky.

The bell from Saint Mary’s rang six in the valley. I hummed out a tune on the toll of its chime.