Give Scandal [extract i]

"Voyeurism is waiting, that is what I learnt from my summer as a voyeur ..."

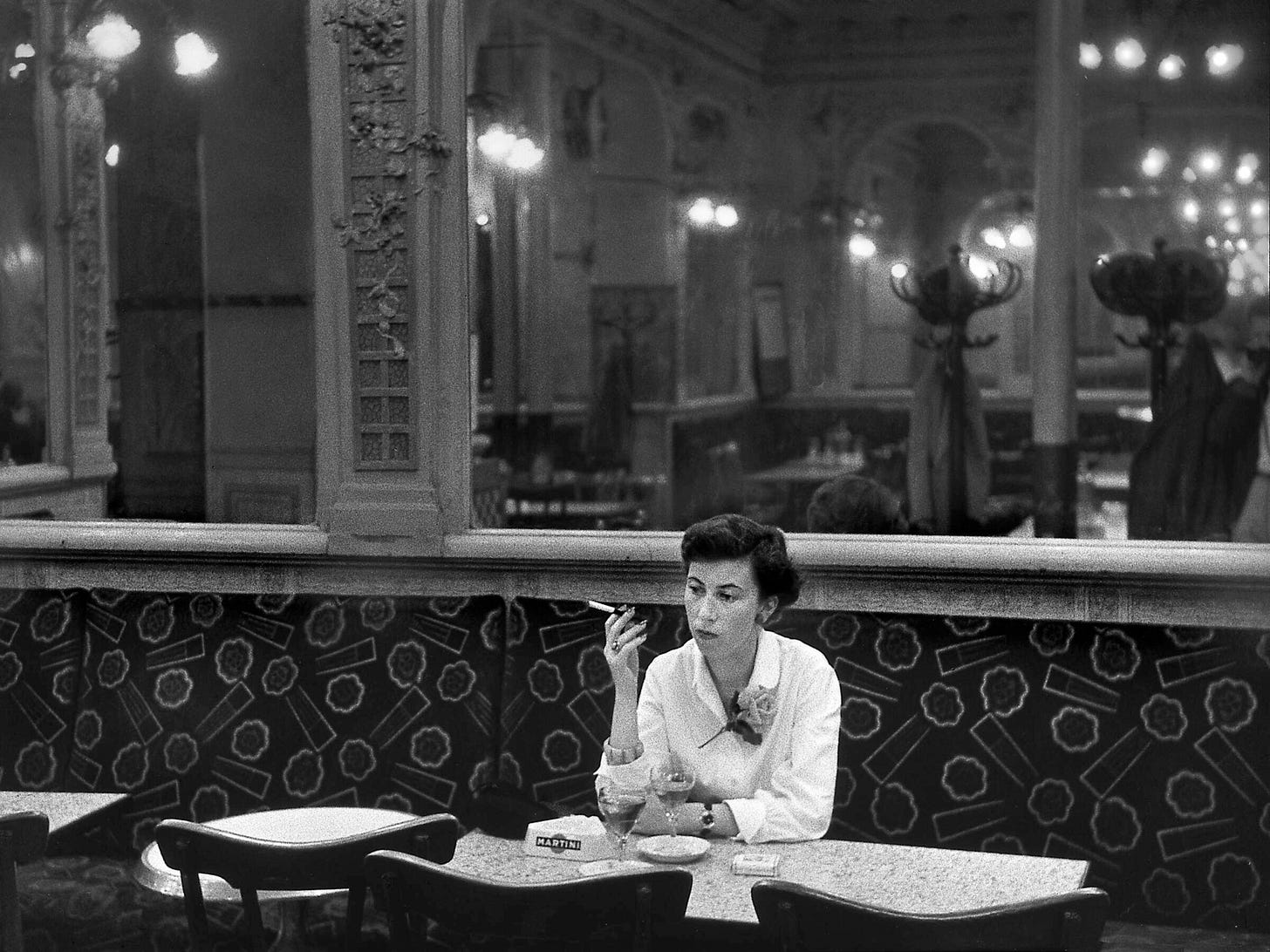

We were in a booth in the brasserie on the corner, not five minutes from where we live. It was mid-afternoon and the place had emptied following the lunch-time rush. We hadn’t eaten together, instead arriving after things had fallen quiet. It wasn’t the first time we had met that way, but neither was it happening frequently yet, it was still rare enough an occasion to be considered a happy accident, a matter of schedules according, work and family commitments — innocent. More so than anything that transpired between us — at least, that is, that anyone observing us would notice — it was the emptiness of the restaurant and our choice of table that hinted at the clandestine. I think, had anyone confronted us, we would have scoffed at the notion that anything secretive was going on, whether that would have been due to naivety or wilful blindness. Why would we choose somewhere so close to home, somewhere we might be recognisable, if we had wanted to get up to anything untoward? I am confident in saying, however, despite what protestations we both would have made, that we knew. I did. And I believe that she did too.

I was in love with her. Perhaps she was not with me yet — and it is possible that she never was — but I am certain, at least, that she knew how I felt, and was willing to accept my love. Willing even to encourage and facilitate it.

We were sitting opposite one another, neither huddled close nor holding hands across the table; we were not playing footsie under it. She had ordered tea and me a coffee, yet another demonstration of our caution — what was unfolding between us unfolded soberly.

I can’t remember what we had been talking about, perhaps some film or a book that she had read. Likely nothing of any great consequence, other than that, whatever the discussion, we shared an ease, to me, of the greatest significance. Such ease in communication was something of which I had always been deprived. Had I never known it, or had it simply been so long that it seemed unfamiliar — unrecognisable? Had it been so long I had forgotten it was something I could want?

As we talked, I must have become emotional, or she must have sensed an emotion in me. I don’t recall expressing anything specific. I don’t recall expressing much of anything at all. I was always a better listener than talker. She must have noticed something in my eyes. Perhaps I flushed. Either way, our conversation faltered.

“You’ve never told me much about yourself.”

It hadn’t occurred to me before, but she was right. I did not speak about myself. Meanwhile, with the exception of anything about her husband, I had learnt a lot about her and her life. I knew her daughter’s name, and her hobbies, and how she was getting on at school. I knew about her siblings and her parents. I knew about her job, its quotidian frustrations, the projects on which she was currently working, her ambivalence on returning after her congé de maternité. I knew about her, a few things about her at least: her tastes, her education, her thoughts on the issues of the day. I knew a little about her childhood, and the village in which she had grown up. I knew how she spent her holidays.

“You don’t usually talk about yourself.”

She wasn’t wrong. I asked her what it was she wanted to know. “Anything,” she said. “Everything.”

I suspected she was curious whether I was married or had family of my own. Enough time had been spent together that the lack of any mention would have been noticeable. Still perhaps, I thought, weighing up how I might respond, to have asked outright if I had a wife, or girlfriend — perhaps a boyfriend or husband — she might still have thought too direct, too revealing of her interest, of too great a fascination with my sentimental life. Perhaps, she thought, she would betray a jealousy she had begun to feel, a crush so intense that it was bordering on obsessive. At the very least it would let me know that she, when I was not around, found that she thought of me, and wanted to fill in the gaps of what she didn’t know.

I certainly found her interest flattering, but there remained a flintiness to it that prevented me from luxuriating in its glow. I could still not quite get over my fear of her reserve, the fear that behind it rejection lurked. Still, I flattered myself further by supposing she thought me too good to be true. We had such chemistry, such connection. I was present, I was available, and I was asking her for nothing. I enjoyed her company, clearly, and despite my propriety, had been unable to hide my physical attraction (how often, in the cinema, my hand had found her thigh). She was probably, I thought, waiting for the other shoe to drop, waiting for the moment I let slip I had a wife, or a long-term partner who worked away a lot, or from whom I was estranged, or whom I no longer fucked: anything to scuff the sheen of the draw she felt. Perhaps she feared I was a charming psychopath, one just waiting for a chance to kidnap, rape, and dismember her. Perhaps she thought I’d lure her into some kind of trap, or I had been sent to seduce her and set her up.

Of course, the most obvious and therefore most probably true explanation of her interest was that she was bored in her relationship. Not unhappy, necessarily — it was unlikely her husband was a brute — but fed up, and appreciative of the attention, willing to indulge it, as far as it went — which would mean, NOT FAR, not beyond cultivating the warm little glow that comes from being desired and holding someone’s eye. An educated woman from a middle class family, a child and likely a second soon planned — such is the model of the secular bourgeoisie — a husband overly committed to his job, who either works away a lot or is preoccupied, one who perhaps doesn’t share her interests, or with whom the spark has temporarily been lost … so cliché.

Aware, in the moment, of all of that — and having thought it all over in hours I could not enumerate, then and since — I can say now, with the benefit of hindsight, that she was right, I had revealed little of myself. There was a protection to be found in distance, and further, which I sought in dissociation. Fear too was almost certainly a cause, a fear of losing through a revelation of who I was what had become more than precious — had become my life itself. I could not risk her knowing either myself or how much she had come to mean.

“Well? What have you got?”

I suddenly found I couldn’t speak. It was not that I did not know what to say. There was plenty to say, relate, explain. Nor was it, in that moment, that I did not want to. I did. There was nothing I wouldn’t have told her then, if, in that instant, I had been able. I may even have admitted to the whole thing, my admiration, my attraction — my love. I would have told her anything and, indeed, everything. Shamelessly even, for the first time in my life. I would have been revealed. But I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t say a word. I stammered.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to put you on the spot,” she laughed, though looking slightly sheepish.

“Not at all,” I coughed.

I had stuttered in the face of an invited love. I had courted her, and she had invited me into love with her, to declare a love, if not in so many words, to love in speech, to allow myself to be loved. And despite how I fumbled, she still encouraged me. With her eyes locked on mine she encouraged me to speak,

“Please,” I said, “it’s not—”

We looked at one another across the table. I looked into her eyes, admitting a wordless love to them, my confession met with warmth and light —

“Come here,” I said. She looked confused. “Not here—” I stood and took her hand, leading her out from the banquette, then I led her to the booth next to the one in which we had sat. I gestured for her to take a seat on the bench, positioned with her back to me. Though still confused she put up no resistance. She didn’t ask what I was doing nor why.

Once she was in place, I brought her cup and the small tin pot of tea and laid them out for her on the empty table. Then I went back to my seat.

Now, we were sitting back to back.

“Ask me again, I said.

“Ask what?”

“Whatever you want.”

“Tell me about yourself.”

I told her everything about my life, sparing neither detail nor my self.