This is a translation of the ‘Postface’ to Le Chemin du Fer’s recent re-edition of Hubert Gonnet’s 1966 novel, Le Grand Scandale. It was written by Christy Magnin, whose research into Gonnet, first done for his podcast, Oublieuse Postérité (which you can find here), was fundamental to the rediscovery of this forgotten masterpiece.

“We are never, it seems, tempted beyond our strength. It is time then for my strength to increase or for my temptation to cease …” [1]

Father Jacques Dupin is not the Uruffe parish priest, who, on the 3rd of December 1956, killed nineteen-year-old, and eight-months pregnant, Régine Fays. He is not Guy Desnoyers, the man well-liked by his parishioners, who gutted his lover having absolved her so he could rip the child they had conceived together from her stomach. He is not “the priest forcefully holding on within this ferocious beast” [2], who baptised the new-born so God would welcome it, then stabbed it and disfigured it to ensure his paternity couldn’t be read on its little face. No doubt, growing up, it would have worn the smile of sin; its look would have been one of eternal terror—that of Isaac coming suddenly to understand that no guardian angel will save him from his father.

No, Father Jacques Dupin is not the Uruffe parish priest, but he is a ringer for him. Everything, or almost everything, in the novel is true. The two priests are formed of the same clay, the fleshless paste that is no more than mud, blood and nothingness. We know very little about the vast shadow pilgrimage that Guy Desnoyers first began with Madeleine in 1946, “rushing, cornered” [3], and concluded a decade later by sacrificing one of his many lovers. The silence of faith. The silence of the trial. Silence in reclusion. Silence in the darkness of the Morbihan monastery which he entered on his release from prison in 1978, and where he remained until his death in 2010. Would the dark night of the Uruffe curate’s soul ever see dawn again?

This is the question Hubert Gonnet attempted to answer in 1966 with Le Grand scandale. A monstrous novel was required to respond to the monstrousness of the facts. An ambivalent author was needed, one who could accept the demiurgic powers of the Creator no less so than the destructive might of the adversary, Satan himself. How to determine the length of Jacque Dupin’s dark eclipse is truly a difficult question. Should it last the duration of the amnesiac period in which the murder took place? From his first relationship? From his childhood and experience with an angel? Should it go on until the death and beyond? An hour after committing the crime, the priest dines at his brother’s place as though it were nothing, a little later he coordinates the search for Rose Médieu; he rings the alarm in the middle of the night, and as soon as he finds the torture victim, falls to his knees and prays like an innocent. Though he doesn’t know it, the four hundred pages of confession that follow are the first hint of dawn’s colours. Long lost to his flesh and now lost to humanity too, he should resign himself to the facts like Graham Greene’s whisky priest in The Power and the Glory[4], “but turning back is never allowed. I am caught up in the gears and must go, inescapably, on to the bottom.” [5] Thus one mistake leads to another greater yet and “there will be no end.” [6] The murder itself is nothing but another tale to add to Father Dupin’s dreadful litany. It is neither temptation, submission nor abdication. It is something else. Gonnet’s protagonist has escaped the traditional dialectic. Even blood-soaked, he never renounces his vocation; he may well be the most loyal of creatures, the Creator’s most loyal monster: tu es sacer dos in aeternum.

It is the eternity of the apostolate, a blessing and a curse, that degrades him and pushes him towards the crime more so than a flaw, guilt or a predisposition to murder. Dupin seems to have understood the portent of Father Annebault, who himself wrestled with carnal instincts in the presence of Nadie Krul in Roger Bésus’ Cet homme qui vous aimait: “Passion snubs you yet passion is the leaven of great souls.” [7] He heard it clearly but took it the wrong way, as a man of God but no less so as a man of mud. He wasn’t lacking in leavening; fermentation was occurring elsewhere quickly enough. But it wasn’t honourable devotion to the mysteries of faith that gilded the invisible flesh of the Spirit. No, it was desire that inflated the dough, as incarnated in his “works” with the young women of the parish.

Gonnet justifies this dive into the psyche of the priest at the end of his novel, defining it as an “attempt at interpretation”. No doubt. As he wrote, he knew the point of departure (“the very famous story of Father Desnoyers”), and, of course, he knew the destination (“his crime”). The author therefore set out to extrapolate “the slope”, to define its axes, its incline, its linearity or otherwise, the scree, blood and tears that marked it out. Armed with this information, in turn, he engages in a kind of manipulation, as divine as it is diabolical, in order to deceive or delight (it depends) the reader. We who thought we were witnessing a soul’s infinite fall perhaps find ourselves, at the last moment, witness to its resurrection.

Gonnet strives, throughout these pages, to make us believe that his protagonist will give in completely, that, from the edge of the world, he will sink into the abyss and, reaching ever further depths of hell, confess that he was wrong, that he has saved no one, and that he is an abject criminal. Yet, in this novel, all the players in the drama are saved. Father Dupin saves Rose Médieu and her child. As for Dupin, Gonnet decides to save him, at least in part. He goes as far as offering images of the Passion at the very end of the book in a scene of Bernanosian possession of a rare intensity—the crowd ready to lynch him taking communion moments later—while, on the righthand page, Dupin’s consciousness falls silent, leaving us uncertain whether it has abdicated*. This is Creation and Apocalypse reunited in the labours of the novelist. It is the Father and the Son brought back together on terrestrial and celestial planes. Ultimately, it is love redeeming all worldly sins. That’s what makes Le Grand scandale such a powerful and ambiguous redemptive novel, one which shares the concerns of Julien Green and François Mauriac, the latter who remarked, also in 1966: “at the moment I’m writing, the Uruffe parish priest has perhaps become a saint.” [8]

[*Le Grand scandale is effectively two novels presented in tandem, with the “external” story of the investigation, arrest and trial presented on one page (verso), and the “interior” story, that of Fr. Dupin’s inner-monologue, set opposite (recto).]

The Case of the Uruffe Curate in Literature

Le Grand scandale crowns with thorns the return literature made to Uruffe every four years. First there was Claude Lanzmann in 1958 with “The Uruffe Parish Priest and the Reasoning of the Church”, which attempted to show that the Church, as far as it could, had tried to take responsibility for the crime so as not to bring the institution down, into the muck, to the level of ordinary people. “If it suffers with him, from him, through him, and in him, it reveals in its way that the priest’s guilt is no less its own. However, this guilt changes meaning: from black sheep, Guy Desnoyers is transformed into a lost sheep, and it is the whole Church that goes astray in him.” [9] This is the theory that the judge Péret, on the left-hand page, supports, affirming that “it’s not the priest who’s guilty, it’s the religion” [10]—a theory the righthand pages sometimes adopt to later refute, one of the levers of the novel’s narrative richness. It is also true that the Church never abandoned it’s priest (though he was stripped of his status), and, in 1978, actively participated in exfiltrating him to the monastery in Morbihan once conditional release had been agreed on by the authorities.

In 1962 came Marcel Jouhandeau’s Trois crimes rituels, which, in an entirely different manner, attempted to demonstrate that “nothing else existed for the man other than the irresistible fascination he exercised over his prey and they on him, to the point he would remain bound to them until the extremity of the situation forced him to reflect, to let go […] nothing mattered to him anymore but fornication” [11], and further to recall the expiatory character of the sacrifice the Uruffe curate committed. He tries to escape the infamous paradox pronounced by René Girard in the opening to his book La violence et le sacré, to wit it “is criminal to kill the victim because she is sacred … but the victim would not be sacred if she weren’t to be killed.” [12] Elsewhere, Jouhandeau is not far from presenting the concept of the monstrous double, which, in the Uruffe parish priest’s hallucinations and amnesia throughout the sacrificial fit, manifests “within him and beyond him at the same time” [13], which is to say in the absolution that saves the mother and the baptism that saves the child, in the outstretched arms, the finger set on the pistol’s trigger, the hand which contracts, which guts the first victim, stabbing and slashing the face of the second. It is this hysterical mimesis that Jouhandeau and Gonnet share. God and the devil fighting in the priest. Jouhandeau decides to drag him “down the slope of a vertical and endless fall towards an oblivion he will never reach” [14], while Gonnet has him walk majestically on towards calvary, throwing a woman to her knees, and invoking joy and rapture.

1966 arrives, and is marked by not one but two attempts to interpret the crimes of Father Desnoyers. This year also gives birth to the first pages of Jean Raspail’s unfinished novel, La miséricorde (published for the first time in a 2015 collection of his novels). In this book, which has “no need for an ending, other than an eternity of silent questions and meditations on the unfathomable mysteries of Faith”[15], the author, in turn, depicts the Uruffe parish priest, this time renaming him Jacques Charlébègue. By its very nature, it is a kind of spiritual successor to Gonnet’s novel as it explores (only partially, alas) what becomes of the priest once he is imprisoned and retreats into the anonymity of a church where he is no longer engaged in listening to confession and helping in “the work of cleansing”, no longer wanting “to see another face, only souls.” [16]

Jacques Dupin and Rose Médieu for Gonnet, Jacques Charlébègue and Rosa for Raspail. The former novel published in 1966, the latter begun in 1966. Though we may never be certain that Raspail held Gonnet’s book in his hands, that these elements might allow us to suppose the first had an influence on the second isn’t nothing. Such an onomastic coincidence seems impossible, and one could wager the post-script to La miséricorde in which Raspail notes “when, in 1966, I was writing the very first sentences, twelve years after the crime and eleven after the trial, the case had long since been forgotten, and the condemned man’s name was never brought up” [17], is nothing but a trick of the memory half a century on.

The meditative silence lasted three decades. Then, Jean-François Colosimo, in a rich and taxing hybrid novel, Le jour de la colère de Dieu [18], reawakened memories of the tragedy, approaching it from a theological angle.

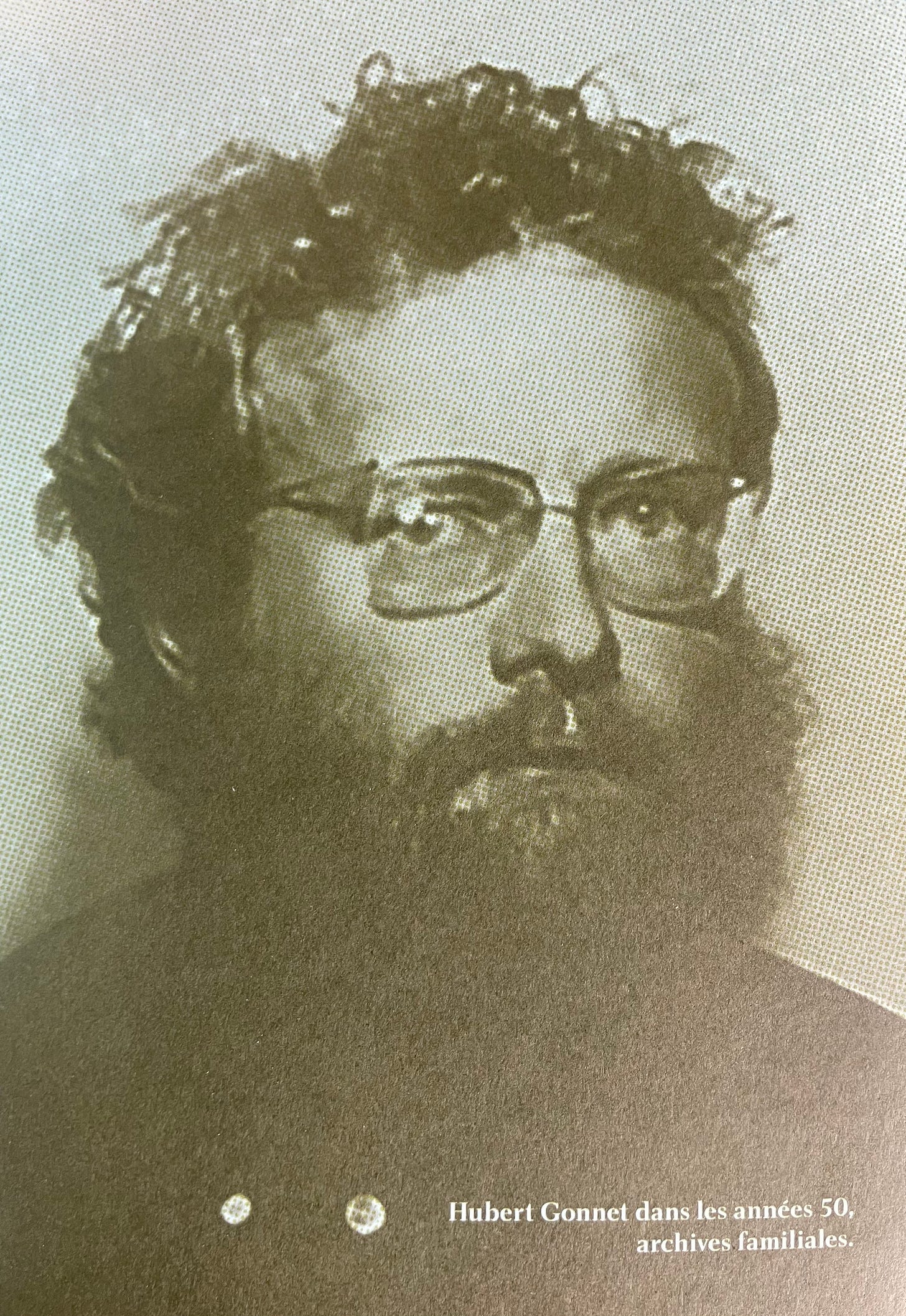

Shadow Biography

Little is known about Hubert Gonnet. He seems, in all honesty, to have gone through his literary life in true solitude. He was born in Picardie in 1924. We know he had five brothers and sisters. Among them were Antoine, called Tony, Gonnet, a Surrealist then abstract painter, who was a character around Saint-Germain-des-Prés after the war. On the streets, at Café de Flore, he hung around with Mouloudji, Jacques Prévert, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone Signoret and more. No less than Jean Genet wrote the preface to his first exhibition in Paris in 1952; Jean Cassou in 1970. There is a wealth of information, articles and photographs attesting to this. As such, we know a great deal more about him and his literary friendships than we do of those of his little brother, Hubert, fifteen years his junior. Up to now, no on is aware of any correspondences. What information we do have is piecemeal, come to by chance through conjecture or uncovered by deduction.

One would be hard pushed looking to Gonnet’s seven novels to crack even the slightest breach. There are no dedications (except to a certain Jacques Anthelme from Marnac in a preliminary draft of his first novel, L’exécution) and a couple of epigraphs from an Yves Querglin (which make sense to a critic but less to a biographer), who appears as both a character (see Un chasseur français) and a pseudonym (used for the unpublished manuscript Les croisés, nouvel itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem). The following epigraph, taken from the manuscript Mort en sursis, which would become the novel, L’exécution, sums up Gonnet’s ambiguity: “Novelistic fiction, like dreams, is almost always the accomplishment of a desire.” Here come the murky mist that blurs the hackneyed border between fiction and reality, providing material for psychologists. Indeed, does L’exécution not depict a man at death’s door who wants, before his final breath, to assassinate the President of France?

What else? A lone homage to Isidore Ducasse, Comte de Lautréamont—his prime forebearer—in his final novel Voyage au Strömland. Obviously, if the meat of the novel is identical to that of the mysterious poet from Montevideo, infernally biting, carnivorous and carnally gorging, a true “phenomenology of aggression” [19], as Gaston Bachelard wrote, it is sometimes even less metaphorical than it is pragmatic. In fact, here and there, Gonnet simply takes a paragraph of Chants de Maldoror to rewrite changing nothing or very little. Immediately shrug off the pale shudder of potential plagiarism. Everything indicates that this superimposition, the reappropriation of the dark genius’ bestiality, is wilful. After all, does Gonnet not evoke in Voyage au Strömland (whose anagram of Maldoror is obvious): “the personal mythology of bears and elephants, hippopotami and vultures” [20], the devasted earth overrun with desecrated corpses and vicious beasts, which is precisely the “animalisation” that, according to Bachelard, contributes to the “inhuman fable” [21] Lautréamont wrote and is perpetuated by Gonnet a century later (Les chants de Maldoror was published in 1869 and Voyage au Strömland in 1969). We are not Surrealists, we are not Philippe Soupault, but in our grimacing slumber, we have probably heard, without knowing it, the hellish poetry lost to the dust of literary history still ringing in our ears.

Escaping the quagmire to find our way back to the marked out path, Gonnet’s literary era began in 1953. The author was discovered by the great editor Maurice Nadeau, who first published extracts from Karl in the second edition of his review, Les lettres Nouvelles, following up with the novel that same year, the first novel to be published in the collection he created in collaboration with René Julliard. The collection’s slogan is clear: “It is intended to gather the works of authors, known or unknown, French and foreign, whether novelists, poets or essayists. Oriented to art as much as to life, it hopes to prove that the two domains are only strangers due to a misunderstanding that would nullify any writer worthy of the name.” In this novel of love and war (selected for the Renaudot), which picks up a theme already explored twenty years earlier by André de Richaud in La douleur [22], that is, a romance between a French woman and a German, it is above all its stylistic and formal propositions that put Gonnet in a kind of avant-garde. Long, punctuation-free paragraphs, mirror games, poetic prose … Gonnet is at a great crossroad between the psychological novel, the Nouveau Roman and “Luciferian lyricism” [23].

Without seeking vain sophistication, he repeated this task from manuscript to manuscript. He attempts a choral novel with Agnès ou l’école buissonnière, tells the story of a building, floor by floor, in Faire le Jacques (ten years before Georges Pérec and La vie mode d’emploi), writes an epistolary novel which provides several endings depending on the reader’s decisions with Un chasseur français … Naturally, we can imagine his work being published by Jérôme Lindon at Éditions de Minuit; Gonnet would hop from Julliard to Plon to Calmann-Lévy, Buchet-Chastel and Éric Losfeld in seven novels; elsewhere, in a vast inquiry into literary creation, L’écrivain et la société, he himself says: “My first book, Karl (1953), was, it seemed to me, to a large degree a precursor to the Nouveau Roman. It was barely noticed. I had no desire to involve myself in any literary trend.” [24] This exploration didn’t end with the appearance of his final novel in 1969, as unpublished manuscripts and novels (from both prior and after) reveal further, original formal experiments.

Gonnet’s lyrical gift, sometimes verging on dark frenzy, putting him in the distant wake of Pétrus Borel and Champavert, Contes immoraux, is unquestionably the strength and a weakness of his work. It is perhaps what brought about the end of his literary existence after seven novels and seventeen years of publications (including a lost poetry collection from 1955, L’autre partie du monde, with a preface from Georges Schéhadé—finally, a link to another author—which praises “this precious soul—made up with lots of white space around each word […] as though each word were cautiously chanced in a void full of magnetisms”, and Green Loves, another collection, written in English, and equally untraceable). After Voyage au Strömland in 1969, nothing more would appear despite the author continuing to write. Gonnet led a shepherd’s life in Averyon.

He died in 1994, leaving among the final pages of his last published novel a cry as Lautréamontian as it is juvenile:

“in the darkness of the tunnel, I struggle step by step, but I’m incapable of advancing. The novel (or what stands in for it for me) has, in my work, always been the expression of a battle, an ever more insignificant battle, by the way, I must admit to my great regret. You would have noticed this if you had made the effort to read me carefully, and above all to compare my different works to gain a view of the ensemble (which no one yet, it seems, has judged worth doing), and uncover the close connections that link them […] where the same characters (with the same obsessive first names) reappear at every crossroad, often, incidentally, slightly off, so the Agnès (or Yves) of one book isn’t exactly the Agnès (or Yves) of another. But perhaps we will only be able to judge that perfectly when all of my unpublished manuscripts are published (if it happens one day, which I doubt). […] What I will maintain, however, is that if the novel is a mirror, it’s a hellishly deforming mirror in which everything must be analysed, interpreted, reconsidered (which, of course, no one bothers to do), and that I alone have the keys (which I have often enjoyed losing) to this voyage to Strömland, which, beneath its constant symbolism, could allow my future biographer (and not the foolish and fragmentary critic) to uncover the adventure the darkness of the text conceals.” [25]

The night of Hubert Gonnet’s work is coming to an end.[26]