“We have a curious way of being dependent on unexpected things”: On Carole Maso’s AVA

(for V.)

“How is this for a beginning?”

I am reading Carole Maso’s AVA on the metro, travelling from the south of Paris to Saint-Ouen in the north, where I will give an English class to an employee of a multinational cosmetics company. Rather than go a more direct route, I take line 6 to Bercy then change onto the 14 which will take me to Saint-Ouen. On the metro map I have pinned up on the wall in my apartment, the Saint-Ouen stop does not exist. There, line 14, the newest of the lines, progresses from Olympiades only as far as Saint-Lazare. This was a perturbing discovery, I had never imagined I would be here so long.

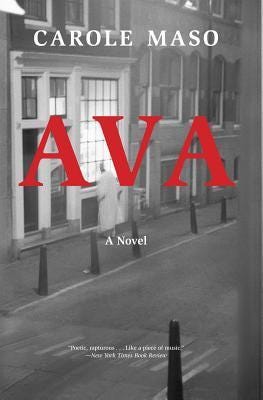

Aside from avoiding Châtelet (something which one should prioritise in any given situation) and the view crossing the river at Quai de la Gare, the benefit of my indirect trip is having more time to read, with fewer interruptions. I am reading Carole Maso’s AVA on a Kindle, as a pdf, illegally downloaded from a forum on which almost any title seems possible to find. I do own a copy of the book, but, for the time being, can’t find it. It was not in the pile of books I had thought it was (though my copy of Carole Maso’s The Art Lover was), which means most likely it is under my bed. Feeling pressed for time, needing to start pulling together the essay you are reading as soon as possible, I had decided I would download a digital copy in order to quickly gauge whether I had anything of interest to say about the book, having been asked by a friend if I wanted to write a little something to coincide with its re-release from Dalkey Archive.

I had loved Carole Maso’s AVA when I first read it, and, at least as much as I was flattered to have been asked, was curious about what the assignment might provoke. Naturally enough, I was also worried I would indeed have nothing of interest to say. It struck me— strikes me— as a difficult book to say anything about, perhaps not least because of how easy it had been to fall in love with, with its rhythms, with the life it so tenderly evokes, with its subtleties, its grace, with its poignancy. How often are we able to say, with any concision or insight, why we love the things we love? We may be able to gesture toward reasons, and even, gifted with a particular delicatesse, avoid the diminishment of our target in the dumbshow, but to what ends? To convince? Persuade? Sell? Understand something about oneself? To share? Simply that, perhaps.

Carole Maso has said that “no other book eludes me like AVA.” [1] That takes the pressure off somewhat. At least, I have decided, even though lacking the critical bonafides, and with a scant interest in academic rigour, I can share a little on what the experience of re-reading AVA now has been, and what it is, as despite the confines of its structure, it is very much a book without an end.

“Let me describe what my life once was here.”

It feels inaccurate to say AVA is a novel composed of fragments, though that is perhaps the most pragmatic description. At age thirty-nine, Ava Klein is dying of a rare form of cancer, and through the course of her last day revisits moments from a life, a stream of brief snippets, sometimes sentences, sometimes short paragraphs, recalling moments, conversations and sensory experiences from a life filled with art, music, literature, travel and arguably, above all, love.

Maso demurs when describing how the accumulation of these sentences produces the effect her book achieves: “I do not pretend to understand how disparate sentences and sentence fragments […] can yield new sorts of meanings and wholeness. I do not completely understand how such fragile, tenuous, mortal connections can suggest a kind of forever.”[2] And I too will defer from offering any kind of stylistic or syntactical analysis which might suggest a theoretical explanation for unquestionable musicality of the text’s unfolding. However, I will return to the notion of fragments and explain why it is describing the novel as being composed of such seems inadequate to me.

Fragments are the panned gold of the discontinuous. Whether glimpsed under the currents of prolonged historical disintegration or within the swell of semantic over-abundance, once sieved, they can be gathered, assembled. The brilliance of Maso’s craft in AVA, whether she was conscious— or would admit to consciousness— of it or not, is that at no point does it feel like an assemblage. Rather, in its flow, it achieves a continuity which if not, perhaps, the continuity of reason, is undoubtedly the continuity of thought, and, especially, as such, for the literary-minded, the continuity of life itself.

As I read Carole Maso’s AVA on the metro to Saint-Ouen, a particular artistic project occurred to me in which one would read the book, note every literary reference, and then read each book or writer mentioned. And why stop there? Why not also make a list of every piece of music listened to, every work of art referenced, then seek out and experience them? Why not make a list of every mention of food, and recreate the recipe? Note the title of every erotic song cycle Ava jokes about writing, and compose it for yourself? Make a list of every country, every city, every single place visited and then head off into the world? The end result of this project would be nothing less than a life— and what’s more, it would not be Ava Klein’s life, it could not be, and would not even be a close approximation of it no matter how faithfully one managed to enact every sentence from the book. Nor would it be Carole Maso’s life, my life or yours, or anyone’s other than that of the person who was able to do those things. Therein lies the beauty of Maso’s text: it offers the experience of life unbound either by arriving at its final page or by death, which itself is surpassed by the object of the book.

“Without inventing a single character, without inventing happenings of more significance than his own simple reality, without taking refuge in inventions of any kind—”

Sometime later, having decided I would make an attempt at the text you are now reading, I dug my copy of Carole Maso’s AVA out from under my bed. How books get stored in my apartment is a simple matter of space, given I live in the smallest (quasi-)legally habitable accommodation available. Books go where books fit: either in one of several stacks, a couple of shelves or underneath the bed. Every so often, I take some I no longer want to keep to the Oxfam bouquiniste on Rue Daguerre (just a few doors down from where Agnès Varda lived), and rejig what remains, a Tetris-like game of reorganisation which can result in books I read not so long ago being buried deep. I must have first read AVA in 2020 or 2021, nonetheless, deeply interred it was with those I had read a long time before. I have been in this apartment now for twelve years; I had never imagined I would stay as long as that.

Going through the books, due to the arbitrary way they end up getting sorted, neither by author or genre but size, is not unlike an excavation. I scrap back the layers of sediment that have built over years of reading. I quite often forget what I have read, so any such reorganisation results in what feels like discoveries or pleasant surprises. Any book still here is one that I have valued enough to keep, and so as the excavation continues my memory is constantly pricked: a book given as gift or written by a friend, one I enjoyed the hell out of, one I bought in the gift shop of a particularly moving exhibition, one I intend to read again, one which is just the kind of thing that I wish I could write. Each book is connected to a person, place or particular moment in my life, and though I may not often think of that, it or them, it is a pleasure to be reacquainted with the memory, even in cases where the memory is not entirely pleasant (that one she gave me, and then she went and left me …).

I reach AVA which, given the dimensions of the Dalkey Archive issue, was right at the bottom of a pile, right in back, against the wall. Finding it has required me to completely empty out the space under the bed. My old saxophone is in the shower; mishappen shoes line the kitchen worktop. The desk, chair, and floor are covered with books; my mattress folded up on itself and wedged into the corner under the slanting roof (if you are struggling to compose a mental image of my apartment given the particulars mentioned above, good). Something not unlike a life has been turned out, not all of one, no doubt, but enough of one that, were you to enumerate the findings in greater detail, would give no little insight into who I am now, have been, and was.

Looking around my room, I wonder of what benefit to the essay I am hoping to write will finding my physical copy of Carole Maso’s AVA be. You may be asking that yourself.

We learn a lot of details about Ava Klein, about her three husbands, her job as a professor, her lovers, her tastes and interests. On any chosen page, one could find a sentence or brief paragraph to cite for its significance, text to a lover or send to someone you care about, or Tweet, say. What I couldn’t do with a pdf is flip, thumb, fan, alighting on a page a random and choosing a random quote:

“Beera, Coca, Fanta, Sprite, amen.

And we walk on water for one night.”

These lines (I cheated, taking two) might mean nothing to you or everything. Or may right now mean nothing but should you come back in a week might have taken on a meaning you could not have predicted. And so with the entirety of AVA, a book the reading of is never over. To go back to pages I had previously read only days ago on the metro on my Kindle, is to find today, slightly sweaty from the search, and grimy too from the raising of dust, a different text, if not entirely so then at least notably. Things get forgotten, slip one’s attention, do not strike in some contexts with the same force they have in others. Moments are forgotten, someone’s absence might temporarily slip our mind, something we have once read may, hunched over, sitting on the bare metal frame of a fold-out bed, strike us with a force we had not felt when the very same words were first encountered. Such is the capricious manner in which significance is allotted throughout life; arbitrarily, unknowably essentially, but liable, when circumstances coalesce to set us in postures of comprehension, to profound divulgence. This is something Carole Maso’s AVA does: shapes and holds us to receive revelation.

“As short as one of these sentences. As brief as that. But with a certain quiet beauty. As seemingly random as it all appears— there are accumulated meanings. I believe that.”

The beauty of a coincidence is what we bring to it. The fact we will notice one at all speaks to its meaning, even when the coincidence in question is banal. That we might share our experience of one, be encouraged to reach out to someone because of one, or feel comforted by one, is secondary to the compliment of our attention. We can decide to act on a coincidence or not, we may keep it to ourselves, even attempt to deny it has significant at all, but it is impossible to ignore the noticing of it.

And yet, the shelf-life of the meaningful coincidence is brief; it carries only a momentary charge. Specific coincidences, I have found— am finding — are difficult to recall. Or certainly difficult to recall without seeming flaccid. There is something too insistently narrativizing about recalling a coincidence. They are too neat; too contained. And the more significant, the more this problem pertains. The thrill in their notice comes from how unexpected the coincidence is, how it reaches us from outside the confines of what our consciousness anticipates, forging a connection to something which, until it is revealed, we had no ability to recognise or predict. Unlike a validated intuition or premonition, their delight is in no small part a function of surprise.

Hindsight lends contrivance, and biases shape retellings. I can relate an anecdote about a particular song coming on in a bar just as the woman I was meeting there arrived, and throw in the fact that, after a period of estrangement, it was the very song to which I had sent her a link when our relationship was rekindled. But so what? Bully for me. It is, perhaps, a cute detail but, I would suggest, as relevant to any given reader as a detailed recounting of my dreams. I could extemporise, describe some more about the scene, talk about how it felt to hear the music come into focus against the background noise; I could sentimentalize and waffle about a fated endorsement of our affair, and how the cosmic design of the universe moved in accordance with my desires, but would doing so be any more powerful than the same scene described in the style of Carole Maso’s AVA:

You arrive late, I thought you had decided not to come. Darondo’s Didn’t I is playing on the radio as you walk in.

Would you have to know the song had been previously shared to understand that it playing had meaning? Would it not be enough that I had specified its name? Would it not be sufficient that you could then go, should you want to, and listen to his song, and draw conclusions from that? Or, extrapolating from the previous sentence, come to your own sense of the relationship we had?

And what if the song already had meaning for you, provoking its own memories? Or if the situation, denuded of so much of myself, of her entirely, our personalities, the period of life we shared, cut loose from the requirements of narrative, the compulsions of reason, a comprehensible transfer from intention to action, from desire to its fruition, want to satiety or frustration, resonated with a situation you had known, might my retelling of it then not possess the same reifying beauty of coincidence, that you have come across it here, by chance, and a connection has been forged?

I think of the coincidences I have known in love—and not romantic love only, but love for friends and family, love for art, for literature, for the city in which I live—and which I can recall at will. There have been many; I have been fortunate. But there are certainly many more which I do not remember. There have been many moments, expressions, experiences, gestures, that re-reading Carole Maso’s AVA in order to write this has brought to mind. That alone should be reason enough to pick it up (or pick it up again on its re-release …), were you looking in reading this for a recommendation.

More than that, however, I see in Carole Maso’s AVA the embodiment of a hope that, rather than merely one’s life flashing before one’s eyes in extremis, we might be granted the grace of reliving our every coincidence with the same fresh and bright-eyed astonishment they were met when they first occurred. It is the hope that the attention we have paid was not in vain, nor was any unremarkable moment, nor any instance to which, with our volition or beyond it, something within us has attached meaning. AVA is a testament to a faith in granting significance, and an enactment of the hope that every case of it apportioning, of love, will return to gild and burnish the life that we have lived.

“Every moment has been a moment of grace.”

Some of you will have read this book, and The Art Lover, and Break Every Rule, and will know Maso and her work far better than I do. Some of you will know Paris, and will understand the necessity of avoiding Châtelet or be able to picture crossing the Seine on line 6 between Bercy and Quai de la Gare. You might know Rue Daguerre, almost certainly you know Varda. You might be able to place me quite precisely in the map of Paris you have pinned to your wall. You might have played the saxophone, or be able to hum Didn’t I by Darondo. All of these references might mean something to you, something absolute, or they may not, or they may have once and subsequently you forgot. This text may have reminded you. It may have set you off thinking about something, or someone, else.

I told a friend I had been asked to write something on Carole Maso’s AVA to coincide with Dalkey re-issue. I was worried, I said, drinking happy hour pints in a bar near Montparnasse, that I wouldn’t have anything insightful to say. For all its simplicity, I explained, it is a complex book. It resists, I speculated, the usual kind of analysis one might lean toward, being both so minimal and so full, so plain and so elusive, so masterfully crafted and yet resonant with energies that are difficult to grasp, or are beyond my ability to do so in text. I wasn’t convinced that I was up to the task.

“Why were you asked to write about it?”

I told her how much I had loved the book.

Sometimes, she said, it is enough, just to share with others that we love a thing we love.

[1] ‘Precious, Disappearing Things’, Break Every Rule: Essays on Language, Longing, and Moments. Carole Maso, Dzanc Books, 2014.

[2] Ibid.